A Year of SQ Lab Testing

Are SQ Lab components comfortable? Are they worth it?

The vast majority of the 700 hours I spent riding bikes in 2023 were on SQ Lab saddles, bars, and grips/bartape. I didn’t expect to be so happy with their saddles that I’d cringe at the thought of riding my prior standard, the Fizik Arione. I didn’t expect to want to keep the MTB bar on my bike even though it’s a bit stiffer than I want it to be. I did expect SQ Lab to deliver quality, reliable products, and I was not disappointed. In what follows, I’ll share my experiences and insights about setups for my summer MTB, winter fatbike, and 3-season all-road / gravel bike. I’ll begin with a safety and intangibility.

Light / Strong / Cheap: Pick Two

SQ Lab’s product differentiation revolves around ergonomics and comfort. Comfort results from the combination of geometry (ergonomics), compliance (vibration and impact damping and absorption), and operation (how we ride the bike). Safety results from appropriate component design, material choice, manufacturing methods, quality control, installation and maintenance procedures., and use within appropriate limits.

Among the SQ Lab products I tested, only the handlebars are safety critical components. In my mind, safety critical components must prioritize structural integrity through the full range of use (i.e., load cycles), from the stresses of ‘just riding along’ to those inflicted when the component is subjected to an acute extreme load (like a handlebar striking the ground during a crash or a very hard landing from a jump or drop). Since we often have to keep riding our bike after crashes, to get back home or whatever, it’s important for safety critical components to ‘break well’ when they break. And let’s be real: we don’t actually want to ride components that can’t break.

With today’s materials and manufacturing methods, there’s no way to build (affordable, at least) unbreakable components that are also light and comfortable enough to actually want to ride. Adding material remains the primary way strength is increased in a given component, which also reduces that part’s deflection and/or deformation under load (i.e., ‘flex’ and/or ‘bulging’ or ‘bending’).

Safety critical components that ‘break well’ don’t sheer into two pieces when overloaded. You can get handlebars from questionable sources online that will fail this way, which can lead to serious injury and death. Those components can and often are both light and cheap, and the truth prevails: you can have two, not all three characteristics - strong, light, cheap. If a safety critical component is strong and light, it HAS to be expensive.

Excellent design requires many iterations by well-paid engineers, and high quality manufacturing is more labour and machine-time intensive, at tighter tolerance levels, all of which come at a cost. This all goes into components like handlebars and forks that don’t snap into pieces when you ride your front wheel into a heavy impact. If these components reach their failure point, fibers are pulled apart while others crush, but the structure, overall, tends to absorb energy as it breaks, more akin to metal bending than dry spaghetti snapping. This means good carbon parts will tend to give us warning when they are failing: creaking, crackling, more flex than usual.

As consumers, we can’t know whether our components are designed for apocalyptic loads, manufactured well, and worthy of putting our faith in. We have to go by brand reputation, word of mouth, and internet research. No brand I’m aware of today markets their bike parts as ‘the strongest’, which is at minimum because it’s impossible to back that claim up (read, intangible), and surely there’s legal risk associated with the claim. Instead, through time, brands develop reputations for durability, reliability, and strength. You have to dig to discern which components will hold up better and best, and the relationship between comfort and safety remains complex.

If we compare comfort between safety-critical components, I think it’s important to try to step as close to apples-to-apples as possible. Meaning, if two components are considered ‘comfortable’ (subjective), I want to know which is stronger, empirically (objective). For illustration, a hypothetical scenario involving two safety critical component options:

Component-A is ‘comfort-level 3’, 200g, $400

Component-B is ‘comfort-level 3’ 200g, $200

How would I decide between these two options? Safety would be the deciding factor; which is stronger?

How about another scenario to illustrate my point:

Component-C is ‘comfort level 3’, 250g, $250

Component-D is ‘comfort-level 3’, 200g, $250

What’s our smart move here? It looks like the D option is better, right? If it’s for a bike that is for Instagram and maybe a bike path ride here and there, sure, grab those ‘free grams’ and enjoy (assuming claimed weights are actual….). If the component is for a bike that will be thrashed, what’s the move? Assume the heavier bar is stronger? But are the listed weights even accurate? Weight Weenies is a resource on the weight side; what about safety? Is there a safety rating out there we can trust?

ASTM Safety Standard - SQ Lab Handlebars

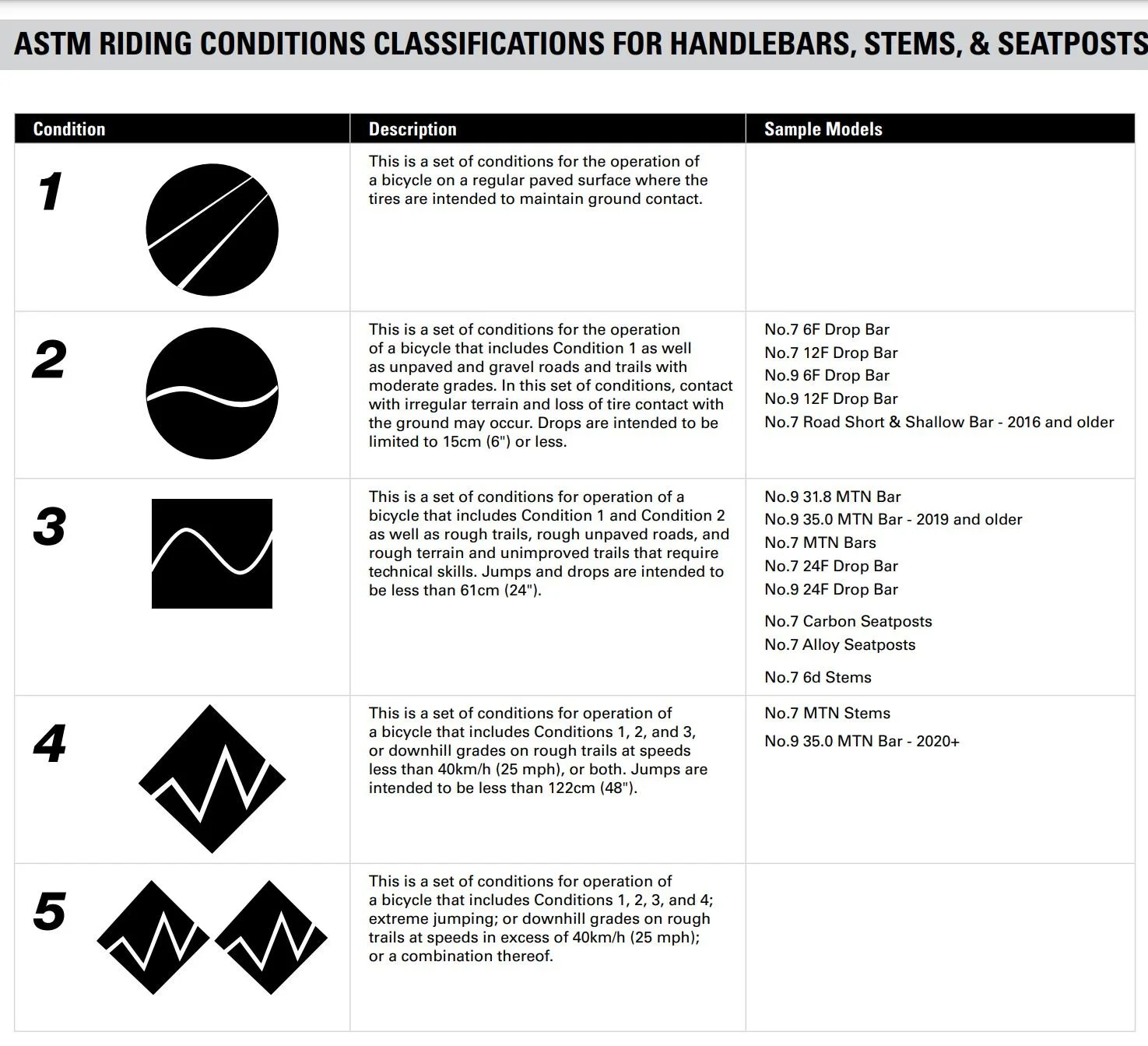

SQ Lab’s transparency about handlebar safety ratings was one of the main reasons I reached out to them in the first place. They provide their ASTM classification for safety critical components, which appear to be more useful to customers than ISO standards.

ASTM standards are formal, technical requirements that establish quality specifications for a wide range of materials, products, systems, and services; they serve as the basis for manufacturing, procurement, and regulatory activities worldwide.

SQ Lab’s 312R Carbon road bar I rode for all of 2023 meets the ASTM CATEGORY 2 (Road) safety standard.

CATEGORY 2 represents the use of….components under the conditions of category 1 as well as on mostly paved and partly unpaved surfaces with a slight gradient. The tires may briefly lose contact with the ground when riding over drops up to 15 cm high (DT Swiss)

Paved and partly unpaved, slight gradient. That doesn’t sound like ‘gravel’ as most of us imagine it, does it?

CATEGORY 1 represents the use of…components on mainly paved surfaces. The ground contact of the tires can be lost unintentionally for a short time.

Ok, so we can infer that road products only need to meet Category 1. What is the ASTM rating for my benchmark Easton EC70 Aero bars? I have no idea; I can’t find this spec anywhere. Does that mean the Easton is likely a Cat 1? I can only guess, and go by feel. This intangible could be more tangible.

What about the 311 FL-X Carbon bar? SQ Lab indicates it meets ASTM Category 4, which “represents the use of…components under the conditions of categories 1, 2 and 3 as well as in very rough, blocked terrain with jumps / drops up to approx. 120 cm height and speeds up to 40 km/h by riders with very good riding skills.” That’s the text I pulled from DT Swiss. They add their “components in this category must be checked for possible damage after each ride due to the high loads. A shortened product life time cannot be excluded.”

I’ve included a table found on Whiskey Bike Co.’s site, which shows the generic ASTM language, with a helpful listing of their components against each relevant condition. I would encourage every brand to follow this best practice.

What relevant comparison to the 311 FL-X Carbon might we make, in the general absence of transparent ASTM information?

One Up produces a ‘compliant’ bar too, and they tend to lean into being open about the safety standards their products meet. I had to dig a bit, and confirmed One Up’s Carbon E-Bar meets ASTM Category 5, which is the highest level and - again, in DT Swiss’s words - “represents the use of….components under the conditions of categories 1, 2, 3 and 4 as well as in extremely steep and rough terrain with very large jumps / drops and speeds over 40 km/h by riders with exceptionally good riding skills. DT Swiss components in this category may also be used in bike parks and on downhill tracks. DT Swiss components in this category must be checked for possible damage after each ride due to the very high loads, since previously caused damages can lead to failure of the component even at significantly lower loads during subsequent usage. The product life time can be shortened by this extreme use.”

This comparison is relevant, because One Up’s Carbon E-Bar is alleged to be noticeably more compliant than most / all? other bars, which they achieve through very deliberate design and construction.

The SQ Lab bar’s claimed weight in low-rise, and at 740mm length, is 198g. Meanwhile, the One Up E-Bar bar at 35mm rise and 800mm length is listed at 238g. However, One Up has not indicated - anywhere I can find - the ASTM for their standard carbon bar, which is the more relevant comparator against the SQ Lab. Should we assume it’s at CAT 5? It weighs less - 220g - and is likely a little more compliant than the E-Bar, so I have to guess that it’s at ASTM 4.

Returning to comfort, compliance is part of the equation, alongside geometry. This brings me back to where this SQ Lab experience began.

Where it started

I hadn’t much awareness of SQ Lab until I saw a post on Instagram from a bike builder and general bike grouch, Peter Verdone. Peter has a lot of strong opinions about MTB contact points, which I respect. Strong opinions, loosely held is a motto I live by. Peter indicated he was very happy with SQ Lab’s 16 degree sweep bars, which I keyed into, as I’d been a bit unhappy with my 8-degree sweep Race Face Next SL bars. They are light and compliant, but I struggled a bit with my wrists and hands over typical rides, which are often more than 5 hours long. I had a benchmark road / gravel handlebar I really liked, Easton’s EC70 Aero, but I was open to being converted to an alternative.

But why carbon?

In general, I lean toward carbon bars because I ride through the winter, and metal conducts heat. This is why I also prefer grips without metal clamps for winter, and non-metal brake levers. Added up, eliminating these metal components really helps hands stay warm enough down to and around -15C, which has become my minimum temperature threshold.

So, when it comes to handlebars, carbon is my go-to material, and the devil in the details. Comfort breaks down into geometry and structural stiffness / vibration damping / compliance. On the saddle side, I am not particular about materials. Whatever yields the support and comfort I’m going for is cool with me. This means I don’t ‘need’ carbon rails, but if they are resilient and damp vibration, while also light and strong, great. If rather stiff, less great, unless the saddle’s shell is configured / structured to float / flex / whatever on a rigid frame. Carbon rails, crashes aside, will have a longer lifespan than metal; carbon can’t change shape over time unless it’s breaking. If you have a weight imbalance to one side, metal rails will accommodate that over time, leading to a tilted saddle, which will exacerbate issues like saddle sores. In other words, metal rail saddles will slip away from their original comfort level sooner than carbon rail saddles, all else equal.

I don’t assume saddles have to be padded much to be comfortable; shells can and have been compliant enough to work well for me with minimal padding. I do assume saddles need to fit our body geometry and ‘use-case’, which might involve harsh mounts (as in cyclocross), accidental body slamming from behind (as in MTB riding), and significant fore-aft butt positioning (as in drop-bar bike riding). SQ Lab’s variety of saddle shapes and widths per shape suggested a high likelihood at least a couple models could work well for me.

Jumping in

On the heels of a really insightful podcast interview with Bastian from SQ Lab, I reached out about testing some of their products. I had a new T-Lab X3 all-road / gravel bike being built, and a 100km fatbike event coming up on the calendar – March 2023. I use the same cockpit components on my fatbike and summer MTB (swap them between, because I have the same requirements between bikes), so I’d have lots of hours to pile on. Similarly, I had two trips to Europe lined up for the new T-Lab, so the testing would be thorough. Speaking with Bastian, he agreed setting me up with product for both bikes would be a good opportunity for SQ Lab, so I made my request, and got into it. And by ‘got into it,’ I mean I mounted product days before the biggest trail mission I’ve ever done on a fatbike: 100km of mostly singletrack! Talk about taking a flyer! I felt confident enough in SQ Lab to send it, and have no regrets. And I spent the time I needed up front to carefully select the products I requested, just as one would do when spending hard-earned cash. There would be consequences if I missed the mark, a perfect scenario to drive insights that would be relevant and helpful to readers.

Measure twice, cut once

Saddles

Step 1, I followed SQ Lab’s measurement protocol before choosing my saddles, so I was not exactly flying blind. I arrived on a 12cm measurement for my sit bones, which is on the narrower end of SQLab’s spectrum (12-16cm), and consistent with my experience over the years with a multitude of saddles that come in multiple widths; I always prefer the narrower options.

I wanted to test two saddles in the same width covering a wide range of riding requirements. One one extreme would be paved and all-road use, where I would lean toward the lightest saddle I get along with. This saddle would need to fit well while riding all bar positions, and in ‘ghost-aero’ mode, forearms on the bars. I wanted to see how much the shape of the saddle determined comfort, versus padding, so I went with the 612 Ergowave R Carbon, 12cm.

As a contrast, I wanted to try a more padded option for fatbike and MTB, where my body position is always going to be a more upright, and I like to avoid a saddle with really thin edges that can mess me up when things go whacky. I held at 12cm width, and chose the 611 Ergowave Carbon. SQ Lab also offer these saddles in ‘active’ variants, which have an elastic (elastomer) interface between saddle shell and rails. It’s easy to believe this would improve comfort, but I wanted to establish a baseline of experience on SQ Lab’s geometry before complicating matters. Meaning, I would assess saddle shape and padding before adding an additional variable.

Handlebars, Innerends, Grips and Bartape

These selections were much easier to make, as SQ Lab sells far fewer bar than saddle variants. For MTB and drop bars, I want the same characteristics: vibration damping and compliance (comfort) associated with materials and construction, and hand/wrist comfort over long hours, associated with bar shape / geometry.

My benchmark MTB has was the Race Face Next SL, 740mm, which is very light and compliant. However, it is not durable on the ends if you run soft grips and clip trees. I had experienced wrist discomfort numerous times during long rides, and suspected the bar’s 8-degree sweep was implicated. Instead of jumping all the way to SQ Lab’s 16-degree bar, I chose the more iterative step: 12-degree.

Paired with the bar, I selected a set of 411 Innerbarends, a quirky solution I’d been curious about for years, having experimented with adapted bar-ends on XC bikes in the past. I also chose two pairs of grips, rather contrasting, to see what a ‘maximum ergo’ grip - 711 Tech and Trail - might be work compared to a more conservative ergo option, the 70X. SQ LAb offers their grips in sizes, which is uncommon, and laudable. I tend to like thin grip material where my outer three fingers wrap around the bar, and a larger diameter where my thumb wraps around. I brake with index finger only, and I find I need a larger diameter for my thumb to keep it from wrapping too far forward, which makes the thumb have to travel further back and forward for shifts and dropper activation. At the same time, thin grip material under the butt of the hand is implicated in hand numbness, so I was keen to see how SQ Lab’s approach - padding added to this specific contact-point - would work.

For a big contrast, I went with the large 711 Tech and Trail, which really amps up padding around the butt of the hand, along with a lot more contour under the knuckle interface. I was particularly keen on these for the fatbike, as it is rigid and can actually be quite hard on the hands when snow conditions are hard and bumpy.

The last element, 411 Innerbarends, would be for summer use, given I don’t spend a tonne of time out in the open on the fat bike.

Hundreds of Hours Later….

There were things I liked, loved, tried to make work, couldn’t make work. Overall, the priority areas I wanted to improve worked out great.

Saddles. The 611 ERGOWAVE CARBON 12cm and 612 ERGOWAVE® R Carbon 12cm are exceptional.

While the 612 R proved too minimal in the padding department for long rides (my sit bone tissue area didn’t love the pressure of XXX hours riding out of Nice in April), I am by no means going to hold that against the saddle. If anything, I think many other saddles with equally minimal padding would have mangled me. The support offered by the saddle’s shape allowed me to be ok on it, while I can tell you Fizik’s Arione in minimal padding variants doesn’t work for me for rides over maybe 2 hours. I didn’t ride on the nose of the saddle (forward, aero position, forearms on the bars) a lot in Nice, but I did later in the year on many occasions, and I was happy with the support.

It’s important to understand that saddle comfort is the result of many variables, which include whether and what type of pad you use, your anatomy, body composition, and conditioning, whether you use chamois cream, your bike fit, pedaling style, power you’re putting down, and the weather. The 612R Carbon is a very light saddle, and indeed the only saddle I’ve used in its class I actually want to keep using. It’s minimal padding can’t retain much heat, or moisture, which is great for hot conditions. Being minimally padded, but well-supporting, it is ideally suited - for me, at least - to high power output riding. In this condition, there’s simply less body weight for the saddle to support; as a general rule of thumb, the more power you push out, the less padding you need, because pushing down also presses the sit bones up.

The 611 Ergowave Carbon was a revelation, and I’ll go ahead and say it’s my favourite saddle ever, which also makes it the ‘best saddle ever’ for me. In essence, the 611 is close to the same shape as the 612, with the exception of being longer. Same ‘shelf’, same width. Key differences include padding - way more - and scuff-protection material around the read portion of the cover, which is perfect for the rigours of all-road and off-road riding.

I gave the 611 a chance to shine right off the bat, mounting it for a first ride that might be considered borderline bonkers: a 100km fatbike trail event. I knew I’d do this, so I used the intense desire to choose my off-road saddle well to drive very careful consideration of options - and learning - and measurement of my sit bones, per SQ Lab’s clear instructions. By digging deep into their product descriptions and rationales for variations in play, alongside careful measurement, I felt I could trust my decision, and SQ Lab’s expertise. These products are not cheap, so it matters to me to know whether fellow riders have a good chance at being happy with their purchases if they, like me, can’t touch and feel product before ordering.

The 100km fatbike ride was amazing, and I didn’t have a single word of complaint about the saddle. It did exactly what I wanted it to do, and was essentially invisible. What a win! On the saddle for 7:52, it was a proper full day, and if you know fat biking, you know that moving all over the saddle is how it’s done, at least on singletrack. Which is what we sure did a tonne of. I couldn’t have been happier with the 611, and this feeling never changed. After my two weeks in Nice in April, I decided I’d swap the 611 onto my T-Lab X3 for my trip to Italy lined up for August, knowing I’d have way more hours stacking up, and a lot of it would be loaded for touring: long days, riding lower power. And I thought I’d have the side benefit of perhaps getting away without having to use chamois cream. Bold.

In a nutshell, it worked out 100%. I rode 6 days, Venice to Verona via Innsbruck, without chamois cream, and experienced zero issues in the saddle zone. I used Castelli’s Premio bibs and San Remo suit, hand-washed each night, both of which use their top-of-the-range pad, the Progetto. Amazing! I continued riding in Italy over the rest of the month, for a total of 111 hours, which were devoid of skin or pressure issues. What an epic win, in my mind. I followed up with returning the 611 to my hardtail MTB, where it was equally perfect. My highlights on the MTB were a marathon MTB race I did in May, narrowly missing my defense of the title in a sprint, then a 150km trail ride in June.

If I’m to make a recommendation, the 611 is an easy winner over the 612, given its versatility. For all-conditions bikes, long haul bikes, it is my new benchmark. The 612 is more niche, the only superlight saddle I’d actually want to ride on a road bike. In my view, its shell is too thin to make it suited to MTB XC racing, as accidental body slamming into it would hurt; thin edges should be avoid on MTBs, IMO.

What’s next? Now that I have set my baseline, I’d love to try the Activewave 611, and get a sense of whether great can get even greater. The 614 Ergowave Active 2.1 is a new model designated ‘gravel’, which lies between the 611 and 612 in terms of shape and padding; effectively a more padded 612.

Bars

Great, not great. This is more complicate than saddles, because bars are about critical safety first, followed by ergonomics, comfort, and aero performance. Regarding safety, which should be your top priority, I have never been more impressed by any other brand’s quality of manufacture. Each bar was flawless to the eye, and very solid in the hands. Safety-wise, this is great; I have complete confidence in these bars to hold up under me. The downside to their robustness isn’t weight, in my mind; I don’t care if they are 50g heavier than other options, for example. Rather, both bars feel stiffer under me than I want.

MTB Bar: Great quality and perceived safety, great ergonomics.

For the 311 FLX Carbon MTB bar, which is 740mm long, this isn’t enough of an issue to be a ‘problem’. Race Face’s NEXT SL bar, same length, it FAR thinner, has a 35mm mounting interface, and is significantly more comfortable in the hands. It is also fragile on the ends, easily damaged. The thing is Race Face pulls off a strong (I believe, at least where it matter most, in the centre and inboard) bar that offers fantastic compliance for about $220 CAN. And, with just 8 degrees sweep, the bar NEEDS compliance, in my opinion. I say this as a firm believer that 8 degrees sweep is not what I or other riders I know need.

I used to run 11-degree Titec bars way back when Azonic and Answer bars were popular, both of which were freakishly flat, but had a lot of upsweep. When I was struggling with hand and wrist issues on my Race Face bars I was pretty sure compliance wasn’t the issue. The sweep was likely the problem, and the bump to 12 degrees felt like a sufficient contrast to assess. Without going all the way to 16 degrees, I’d have a good chance at parsing out how much sweep was doing for me, independent of flex characteristics.

In simple terms, there’s nothing about the 12 degree bar I can pick on as needing fixing. My wish would be for more compliance out of the bar, holding to its level of strength. Whether this is achievable for SQ Lab at a reasonable retail cost, I don’t know. And whether bumping up to 35mm for the clamping area would help, I also don’t know. If I have opportunity, I will absolutely submit my suggestion.

Dimensionally, I am comfortable stating I think 740mm is an appropriate width for this bar’s intended use, and I believe we get into diminishing returns as we go wider. I’m 6’1” / 185cm, and I can tell you I don’t have any interest in more width. The wider you go, the less range of motion you have to work with in your arms, and range of motion underpins bike control.

There’s not much to say about stems. The 80X Ltd. in 50mm is very well made, and uses chunky M6 bolts, which says something about its intended use; this is not an uberlight XC stem. It’s not a looker, but performed flawlessly, and is lighter than it appears. A side-benefit to the 31.8 spec here is compatibility with Jack the Bike Rack, which I’m using for load carrying on my dropbar bikes starting spring, 2024. It’s a 31.8 clamp, ultra versatile.

Bottom Line: I recommend the 311 FL-X Carbon bar, acknowledging that its retail price, $339.99 CAN, is well beyond comparable carbon bars at around $220 CAN. My carbon requirement, which is about cold, primarily, is always going to drive cost up. At present, I’m not aware of any other carbon bar on the market with 12, let alone 16 degrees sweep. If you also want or need carbon, and are set on 12 or 16 degrees sweep, its not possible to compare this bar against others in terms of value; it’s the only one. So it’s more a matter of whether the quality of the product feels appropriate against its cost. I find no faults in the product’s quality, and if I’d paid for it I don’t think I’d be sore about it. When push comes to shove, this equation comes down to whether I’m confident other riders will also consider the bar faultless. I’m confident in this, so I’m comfortable telling you, dear reader, and my friends alike, that these bars really are excellent, and you won’t regret the spend.

What’s next? I will continue to use the 311FLX Carbon bar for as long as possible. If SQ Lab release a more compliant version, I’ll be more than happy to try it. I’m curious whether the 16 degree variant would be even better than the 12 on the longest rides, and if they are keen to provide one for testing, I will do.

Road Bar: Great quality and perceived safety, shape is not for me.

Structurally, and in terms of quality of construction, these are 10/10; great. Against my benchmark bar, Easton’s EC70 Aero, the 312R Carbon strikes me as definitely stronger in the context of a crash. If you want a carbon bar that can take the rough and tumble of cyclocross, for example, I’d recommend this one over any other I know of. All we can go by, however, is this bar’s ASTM rating; the absence of information from most other brands isn’t helping. However, there is a close comparator in many respects, Whiskey’s Spano bar. This bar has a strikingly similar geometry to the 312R, with the exception of its flair. The bar is rated at ASTM 3, which is a step up from the 312R’s ASTM 2. However, Whisky does not list the bar’s weight, so it’s difficult to compare apples-to-apples. It’s good to see there’s a relevant bar for comparison, however; weight can be determined fairly easily.

Ok, so the 312R comes across as a robust bar, made really well. What about its ergonomics, which are what the bar is all about? The bar’s ergo features boil down to the following geometric moves:

backsweep on the tops, with a non-round cross section to distribute weight across more surface area;

ergo drop shape: curve radius has a flat section, and the tube is flattened on outside of the grip section (‘angular and areal’)

recess under the flats for your fingers to grip

deep flat section to spread weigh over

slight flair at drops - 1.5 degrees

The bar’s geometry was hit and miss for me. Over the year I experienced a lot of hand numbness while riding on the hoods, which I suspected my 11-speed mechanical levers were responsible for. Could the bar’s rigidity be amplifying that? Hand numbness can arise from a range of issues, bike fit being the primary one. My baseline setup was SRAM’s HRD 11-speed levers on the Easton EC70 Aero and a variety of other bars, so I couldn’t parse out how much of my discomfort was about the levers versus the bar itself. I ended up experiencing the same numbness with the GRX levers mounted to my Easton bars, so I’ve ruled out the 312’s geometry being a driver.

One thing feels fairly certain: the bar is stiffer than my benchmark Easton. My fork could be stiffer than some of the others I ride, but I’d likely feel that under braking load too, and I didn’t notice anything there. I was hoping the bar’s somewhat flattened top would provide a significant amount of vertical flex, but it isn’t surprising that its taller cross-section is more rigid than the Easton. For reference, I’m 185cm / 6.1” tall, and around 175 lbs, plus kit. I think its likely the two lever types I’m riding in 2024 (GRX 11 and Campagnolo EKAR) are bad for my hands, and make any bar feel stiffer than I want. Keep this in mind when comparing bars.

The ergonomic shaping SQ Lab executed didn’t quite work for me. The flats were too shallow to spread out weight as well as I’d like while riding with my forearms on them (aero position). While placing hands on the tops, I would normally be climbing, not bearing down with all my weight. So the recesses under the tops for the fingers were irrelevant; my fingers wouldn’t wrap around that much. And, I routed my cables externally for ease of maintenance and best derailleur cable performance, so some of that indentation was occupied anyway. If these recesses necessitate more material elsewhere to meet ASTM 2, I would submit that it’s not worth it. If a flush section would enable more bar compliance, it would be worth it. At the same time, I understand that compliance and comfort are intangible, while features such as this recess are tangible. This is why I would strongly advocate for standardized testing and ratings for compliance quantification. I’d love to see reliable metrics for bars, forks, and seatposts.

Still on the ergonomic shaping front, I didn’t get along with the drops’ compound bend. This ‘ergo bend’ approach works for some folks, not others. For me, the issue is that the ‘flat’ mid-section of the drop’s bend reduces the range of position I can put my shoulders into while maintaining a comfortable wrist angle. The bend essentially provides one ‘optimal’ hand position, which translates to one optimal forearm position, elbow bend angle, and shoulder position. As I move my hips fore and aft, my hands need to be able to move fore and aft along the drops too, and without kinking my wrists. This grip section’s flattened exterior face was muted by my bar tape, and I’d consider it neutral. I note numerous other manufacturers doing the same thing with their carbon bars now, and my take is that it’s meant to be a low-to-no added manufacturing cost option that creates a feature that can function as a product differentiator. Does this shaping matter? I can’t say for sure, but I can say I won’t seek this feature out in the future. Folks who like to ride in the drops a lot, and position them high for this purpose might find the compound bend great.

Bottom Line: The 312R Carbon bar is well manufactured, and might be one of the stronger carbon bars on the market. The bar didn’t work well for me from a comfort perspective, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t or won’t work well for others. If you’re riding a bike that feels a little vague in the front end, you might actually wish to use the 312R to increase the bike’s feeling of precision. If you ride in one drop position, the bar’s ergo shaping might be exactly what you’re after. Lots of folks swear by ergo bends with flat sections, so it’s fair to say this approach is exactly what many folks want. SQ Lab released a new iteration of the 312R after I’d spent a few months on mine, and it remains to be determined whether the update renders the bar more compliant.

What’s next? I’ve removed the 312R and am setting my bikes up with my baseline Easton EC70 Aero bars. If SQ Lab’s latest iteration of the 312R is meant to be more compliant, I have a tertiary bike I can mount it onto for testing. If such a bar is in development for future release, I’ll be happy to test it when the time comes.

Bartape, Grips, Innerends

I’ve packed a lot into this post, so I’ll keep this section as short and sweet as possible!

SQ Lab’s 712 bar tape (34,95 €) comes plenty long for overwrapping or 46cm bars, and is middle-of-the-road in terms of tackiness. It’s easy to install, and feels good with or without gloves. In really sweaty conditions, it’s again mid in terms of grip. I didn’t use gloves through the hottest riding I did in 2023 (Italy in August), and I found the tape fine. It’s hard to quantify the tape’s shock and vibration damping, but I’d put it a little lower than the ‘most’ I’ve ever used, from Silca. The only notable thing about the tape was the delamination on the left side that developed after around 300 hours riding. That was unusual, but at the same time, I slid the bike out in Italy and shredded the take on the other side, and it held up really well for the rest of the year. Meaning, it didn’t disintegrate, and I was able to push it to the end of the year. Bar tape is a very personal choice, and there will tend to be a few options that suit each rider really well. I like the 712, and have to wonder whether the delamination was an anomaly, since it only occurred on one side. About 100 hours into another roll of the tape in 2024 on another bike, I see no signs of degradation.

I chose two rather different pairs of grips to test the extremes of SQ Lab’s approach for technical off-road riding. The 70X grips in Medium (29,95 €) would be the closest thing to a 1:1 comparison to other grips one would tend to use for a broad range of MTB riding. I’d been using Absolute Black’s silicone grips for a while, which I like, but I’ve used a vast variety of grips over the years. The 70X would have some contour and padding to differentiate them from the vast majority of other grips, and they were different enough from the Ergon’s I test way back to lend confidence that I wouldn’t be bothered by a big ‘pad section’ interfering with my fingers wrapping around the bars. For a significant contrast, I went with the 711 Tech and Trail (34,95 €) in Large, with an eye to using the thicker padding and overall larger diameter to boost hand warmth on the fatbike in the winter, when I’m less sensitive to grip volume. I also reasoned that the rigid bike could use a bit more padding to deal with the thumping one can take on trails that have been ravaged by foot traffic.

It’s difficult to say with utter certainty that the 70X is the best grip I’ve used, but it feels that way. It could be the contribution of the 12-degree sweep bar, or that could be irrelevant. Whatever the case, I now measure other grips against the 70X; it’s my favourite. The 711 Tech and Trail is really interesting, but my hands and wrists seem to need some convincing. I want to love them, but I’m not there. Since I went up in size, I can’t tell what is driving my inability to sync up with them; is it the overall volume or the padding and contour geometry? One thing seems likely: if I was trekking I’d be more comfy on the 711s. This is because I’d have my hands resting on the top of the bars more often, which changes hand angle. The 711’s under-palm padding is almost ‘corrective’ in its geometry, as it slants downward inboard. This makes the elbows want to wing out, which is probably great for folks on narrow bars, but at 740mm, my elbows are already doing what I want them to do. When testing thumbs on top of the grips, that ‘winging’ is countered.

I think the 711s are really interesting, and have a lot of potential to work great for all sorts of use-case. For technical trail riding, I suspect most folks would prefer a size smaller than Large. I’m 6’1” / 185cm and have L/XL hands, so these are pretty girthy. I’d like to try them in Medium and see how they compare to the 70X in that size.

Overall, grip quality is great, and I only have a bit of noticeable wear on the 70Xs, which have 100+ hours on them. I tried a pair of Race Face’s new Chester grips against them in January - February, and felt pretty certain they were less comfortable beyond 2 hours. I will be happy to continue using the 70Xs, and recommend them highly. The Lab folks have recently released a new version, the 70X 2.0 Pro, which is updated with a new rubber compound for vibration damping improvement, and a bit of a tweak to texturing for grip. I’d be keen to test and report on them.

The Innerends are legit; I love them. They look dumb, sure, but their odd appearance says something about the rider: ‘I don’t care how this looks; I’m all about what matters: comfort and efficiency. That’s what the Innerends are for. I mounted them inboard of my levers first, which was ok, but they feel better right against the flange of the grips. This allows the pad of your hand to rest on the grip, not hard stuff. I used them a LOT, and the position is unequivocally more aero than what can be safely achieved without them. They were secure enough on the bars to hold position well (friction paste is included to help with this too), and they are essentially a set and forget component.

If you’re wondering WHY?, and you’re familiar with old-school MTB tech, you’ll remember bar-ends. What were those for? We used to say, ‘Leverage, they help you climb’, which was true, but not very accurate. MTB bars were really narrow, a trend driven by BAD geometry (adapted road bikes) that demanded short bars to steer long stems. Even with long (130-140mm) stems, these bikes had such short front-centres, it was often tough to weight the front wheel enough to steer up steep climbs. Bar ends allowed our hands to move forward, weighting the wheel. While standing and sprinting, our hips would be further forward than the ‘attack-position’, so the longer reach would essentially allow us to break even in terms of reach, versus having our hands too close to our hips and losing leverage. Bar ends were a compensation for whacky bikes, and today MTB bars are way to wide for bar ends to make sense. However, the downside to that width - versus old-school bars - is that our body positions are bad in the wind. As modern MTBs are returning to being really good tools for endurance riding, and a mix of surfaces, aero options increasingly matter. The reality is that really good marathon-style MTB tires roll well on pavement, and against a gravel bike, the main downsides to the MTB are body position and gearing. The latter issue is now easy to address - 11-51 cassettes are available for inexpensive mechanical set-ups - so we can use plenty big chainrings if we want. So aero is now the significant distinguishing factor, and Innerends help with this. Moving the hands in on the bars is the first way to reduce frontal drag. The Innerends are a security-adding device, which make it much harder to knock your hands forward off the bar while dropped low, elbows tucked in.

I used the Innerends inboard of my controls to test the limit of their utility. For comparison, I’ve used actual bar-ends in that placement in the past for endurance MTB races, like 24hr events. That worked well, but that setup is less wise on a modern carbon bar (potential safety concerns). Also, that’s a look that is sort of ‘race-only’, while the Innerends are less ‘out there’ weird. Placed against my grips, I use them all the time. So far, my longest day on them was a 150km multi-surface ride in my region, which included 80-ish KM of singletrack. I didn’t love resting my hands on my controls, as you can see below, so I moved them outboard after that ride. This way the hand rests on the grips, which is more comfortable; this translates into being able to ride the Innerends more over a day, which I believe is more efficient than the alternative, which is more aero.

Next steps

Bar tape - I’ve passed on feedback to SQ Lab. After about 50 hours on the second roll nothing has come up.

Grips - would like to test the 70X 2.0 Pro and 711 T&T in Medium. A pair of 710S would be really interesting to try for bikepacking, which I have plans for in 2024 on the MTB. After all, with lock-on grips, there’s no need to run one style for all the riding you do on a given bike in a year.

Innerends - there are subtle differences between the 411s and 410s. I couldn’t explain these differences from looking at the specs, but I’m happy to try the others so I can better advise.

Closing Remarks

Cycling is growing in popularity for numerous reasons, with new riders joining our ranks across the full spectrum, from commuting through fatbiking and performance road riding and racing. Product marketing is increasingly accentuating ‘features’ in ways that parallel electronics like cell phones and laptops. Planned obsolescence is the norm in the case of electronics, and we’re seeing the same permeate cycling technology as electronics are mainstreamed into drivetrains. Not everyone perceives, or is comfortable with increasing disposability of products made from high-quality materials and plenty of embodied energy and carbon.

Clearly, I’m not comfortable with non-serviceable and unsustainable cycling products. I was drawn to SQ Lab because I perceived a commitment to long-lived products and transparent communication of safety standard compliance. These products are not glamorous; my riding buddies have not said, ‘Wow, cool, you have those new SQ Lab bars!’, or anything remotely like that. The products don’t make themselves conspicuous. It’s been conversations about comfort on the bike that have raised topics like bar and saddle geometry, which implicates ‘flex’ and resilience, and thus, safety. Everything is connected. And on the topic of product support, this is excellent:

For irreparable damage to your SQlab product caused by a crash, we offer a 50% discount on the MSRP of the returned product when you purchase a new SQlab replacement product. (LINK)

I look forward to branching out into more hours on variants of the products I’ve covered here, which I’ll share insights about. If you have specific questions about SQ Lab’s offerings, please don’t hesitate to ask below on via social platforms I’m on. I’ll do my best to help.

Thanks for reading!