Duration, Path, Outcome: The Long Game

I wrote Duration, Path, and Outcome in January, 2021, then forgot about it until I started seeing ‘duration path outcome’ second only to ‘gravel bike geometry’ as most-searched keywords that led folks here to the site. I took this as a sign that the concept is resonating with many, and I ought to follow up on my promise to write about how I applied it to orient three exploratory phases of endurance cycling progression in 2020. In so doing I seem to have uncovered a few specific insights around why riding my bike long and far in 2020 wound up helping me maintain my mental health and well-being in a way that distinguishes cycling from any other endurance sport.

I think many cyclists feel guilty about the time they spend on their bikes. It’s common to hear riders say cycling helps them clear their head and relieve stress, and some proportion of these folks surely believe it. Others worry that they’re just providing a socially acceptable rationale for a selfish endeavor. I bristle at the thought that I’m selfish to ride bikes often and for long durations, because cycling is woven into my identity and I tend to feel like the best version of myself when I ride bikes. Characteristics I care about manifest through riding, and I value the quality time I spend talking with friends about their lives as we pedal side-by-side.

In what follows I hope to convey how and why cycling for long durations and in an ‘open manner’ is a practice that supports mental health and well-being. From this basis, I’ll walk through the steps I took, within the constraints of the pandemic, to shift into practicing the art of the possible in a way that was highly adaptable and scalable. It’s one thing to say, “Just move,” and a different thing to feel good about taking the time and building the confidence to venture into the unknown. If what follows helps just one of you reading, my time has been well spent.

Move the body, and the mind will follow.

2020 taught me that when we’re struggling mentally, the best thing we can do to shift into more positive and hopeful states of mind is move our bodies in different ways. In simple terms, move the body, and the mind will follow. This isn’t just about kinetic movement, but also putting ourselves in different spaces.

There is an interesting principle that states, “You cannot control the mind with the mind. What you should do instead is to look to the body. The nervous system includes the brain but also all the connections to the body and back again. So, when you can’t control your mind, you want to do something purely mechanical, like the physiological side. Once you take control of the body in that way, then the mind starts to fall under the umbrella of this top-down control. – Andrew Huberman

The more experienced we are as cyclists (and endurance sport practitioners in general), the more ‘purely mechanical’ our body movements become. Even if we focus on how we ‘re moving, our ‘thinking’ is somatic and about now, not about later. Our breathing is about what we’re doing now, as a body, not what we could, should, or might, be doing in the future, or have done in the past. Hours of somatic awareness and decision making guided by ‘feeling’ frees the mind to open up to possibility and creativity.

Self-demonstration

In every moment we literally see a path ahead of us, and feel ourselves succeeding in navigating that path in harmony with relevant constraints (power available to put into the pedals being a primary constraint). We can both travel the path we’re on and imagine options for our next turn, based on how we feel, and how we imagine various options ahead will make us feel. In this context, we can imagine multiple scenarios and strategies for managing our resources to '‘succeed’ in whatever way we define ‘success.’ This could be achieving the full route we hope to ride, even if we have to walk a few climbs and drink a Red Bull with 20k to go. Or, it could be dialing the route ambition level back, riding every climb just shy of hard, and reaching home feeling good and already looking forward to the next ride. Each ride presents an opportunity to be creative, define success, and adapt to ensure that we return home happy. Content. Satisfied. Fulfilled. Whatever it is, it’s good. We demonstrate to ourselves that moving freely changes how we feel in our bodies, and how we perceive possibility. We are not powerless.

Constraints drive creativity, if….

How do duration, path, and outcome figure? They are bound up with creativity, which is often suppressed when parameters or constraints on our options (for being and doing) block us from pursuing the path we hold in our mind, at minimum on the subconscious level. ‘Reality,’ as we each perceive and experience it, is constructed in relation to the imagined path we maintain, and this construction biases our perception and awareness toward ‘relevant’ inputs. Meaning, the sort of person we believe we are, and the path we imagine unfolding in front of us determines our personal reality.

When constraints on what we can do to progress along ‘our path’ are ‘imposed’, we will struggle until we can first accept that the path we thought we were on is no longer possible, then create a new path - or multiple paths - that are compatible with the constraints that lie outside our control. By assessing what we can do in the context of constraints, we open ourselves up to creativity. We have to think differently, which begins with accepting loss of an imagined future, then moves into exploration and interaction with the art of the possible.

Professor [Andrew] Huberman says the brain is typically focused on 3 things: duration, path and outcome. What am I doing, where am I going, and what’s the point?

If you want to increase your creativity, you need to think of new variants on duration, path and outcome. These 3 things are rigidly followed in states of high stress or high focus. All you can think about is: How’s this going to happen? How will it turn out?

These 3 things become loose during deep sleep. That’s why when you emerge from sleep you may have new creative ideas. The transition out of sleep is when creativity arises. - Daniel Zahler

Under the weight of uncertainty and a spring of restrictions on where we could ride bikes, I wanted to feel excited about riding again, like I was creating adventures. But they couldn’t be ‘risky.’ Novelty could be the key element, exploration within ‘reasonable bounds.’ Riding to somewhere, rather than creating new variations on loops I could ride from home in a day would be the ideal approach. Simplicity was key; just start doing it!

I used a few simple constraints to help me generate ideas about what I could do. First, I wanted to do rides that spanned at least two days. I wanted to use the gear I already owned, so I’d feel like I was ‘riding’ versus ‘slogging’, and I wouldn’t spend energy fretting over what I had but didn’t like, what I didn’t have but needed, etc.. I already had the kit I needed to do simple overnights with indoor accommodation, so I could build off that.

Second, I’d explore places I could stay that didn’t require long pre-booking intervals. People were fleeing the cities, and it was already tough to book a roof anywhere I’d want to ride.

Third, I wanted to ride routes that would be novel, but not risky in terms of mechanicals and crashes. I’d be solo most of the time, so I needed to risk-manage.

Fourth, I wanted to enjoy each ride as I rolled, versus post-hoc, Type-2 fun style. I wanted to be able to stop and enjoy beautiful spots, bakeries, whatever, versus feel like I was on a mission. If I was in the headspace to ride fast, cool, but I wouldn’t construct routes that required me to ride fast or else wind up in darkness.

Last, I wanted to bias as much as I could toward riding through beautiful places, and experiencing small communities I’d never encountered. After the first ride or two I’d look at adding an additional ‘constraint’: daylight hours in relation to total distance covered.

I began with a relatively ‘simple’ ride into the Laurentians, then ramped up to the next step at two-week intervals. Every other Friday I did a big ride. Phase 3 was the pinnacle of the season, and from there I dialed back to ‘more reasonable’ rides. Though 200km on winter solstice might not qualify as ‘reasonable’……

Phase 1: Just start doing it - Laurentians-bound!

Phase 2: 300km for the first time - Point-to-point

Phase 3: 300km+ ‘fast’ - Ottawa - Riviere Rouge Raudax - Ottawa

Phase 1: Just start doing it - Laurentians-bound!

With the help of friends, I devised two options for flexible accommodation, which I could ‘slot into’ on short notice. The key to making the overnighter thing work was going to be flexibility. If my work week went well enough, my family was fine, I was healthy, and the weather was good, I could line up a plan on Wednesday or Thursday and be rolling from home on Friday morning. Duration would be two days, simple. And it wouldn’t really matter how long I spent on the bike each day.

My friend, Benoit Simard, lives in St-Sauveur. Ben rides on Fridays, and has extra space at his house, so he welcomed me to ride over whenever I could. This open invitation allowed me to focus solely on ‘when,’ and ‘how’; the geographical aspect of my outcome was defined. The how part (aka ‘path’ in the non-literal sense) would be oriented by my other key outcome: a pleasant experience on the bike, free of stress. Just pedal. Feel good.

Meet me in Cheneville! Ottawa - St. Sauveur All-road - 201km

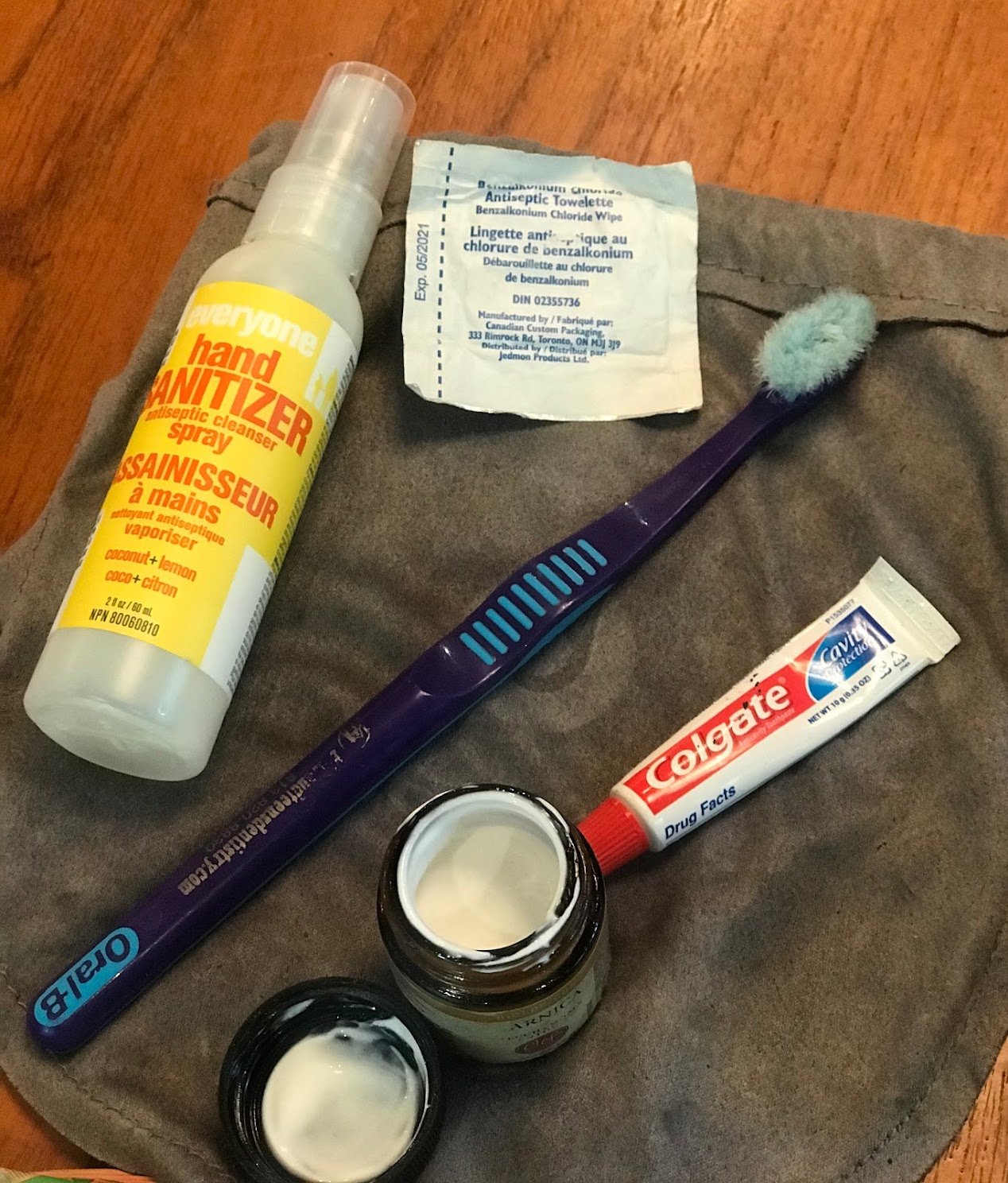

Not knowing the roads between Ottawa and St-Sauveur well, Benoit’s suggestion to meet at a mid-point on a Friday was perfect. All I needed to do was chart a course to Cheniville that I could ride at a predictable pace, and from there Benoit would navigate us through an interesting route to St-Sauveur. Since I’d stay over at his place, all I needed was something light to wear off the bike, toothbrush, and a couple chargers for devices. We’d have access to liquids and snacks along the way, so there was no need to pack a whack of food.

The photo above captures how I rolled from home. My spare shorts and t-shirt are in my handlebar bag, along with chargers, etc, while my tools are in my saddle bag. Tubes and pump are strapped to my frame. I have an external batter packed to keep my Garmin going past about 7 hours. I’d handwash my kit in the shower, put it in front of a fan, and it’d be good to go the next day. This setup is only a little heavier than I use for a typical day out on the bike, so it still feels like ‘normal riding.’ Except I’m going somewhere new!

My ride to Cheneville was straightforward and free of stress. There was no pressure to ride particularly fast, since Ben and I would wind up hanging out a bit in town, which has a great little bakery! That was all I really needed - a few treats - aside from water, and there’s a fountain at the nearby church. The roads got interesting quickly from there, and Arundel, which falls at about 140km, is home to a great cafe with a nice range of healthy lunch options. It would become the mid-point for a bunch of subsequent rides.

We transition to the Corridor Aerobique next, at km 133. What a gem! It ultimately connects up with Le P’tit Train du Nord rail-trail, which is famous for good reason. You’re never far from a good coffee and tasty food on the Train du Nord!

A relatively ‘easy’ 200k day, it felt great to ride through so much new terrain with Benoit, and spend time with him and his family that night. If I’d needed to go out for food I’d have strapped a pair of flip-flops to by bag; bare feet sufficed.

Returning to the overarching concept - duration, path, outcome - the way I experienced my day was oriented by the outcome I had in mind: enjoy a day on the bike. taking in new sights. From this orientation, duration didn’t really matter; it would take as long as it took. My ‘path’ - the ‘how will I get to my outcome’ - part wasn’t about making it through to a ‘result’. My objective was to enjoy myself all day. By setting a simple destination to reach, and be able to ride without any need to navigate after meeting Ben, odds were stacked in my favour. The path I set was in harmony with the outcome I wanted to manifest, and had a lot of contingency built into it. In other words, I didn’t need a bunch of luck for my plan to work out.

Day 2 wasn’t a simple ride back home, but a fun alternative: Scott, Mike, and Simon drove from Ottawa to meet Benoit and me in the morning, and we rode a great route in the region together, then drove back to Ottawa. This format made it ultra easy for the guys; they didn’t have to plan anything, just rock up with what they needed for a day’s ride, and away we went. This was a great way to get them acquainted with the area in a no-stress manner. Benoit peeled off early to do family things, and we capped the ride with a dip in the river near St-Adele, and some coffee and snacks at the Espresso Sports cafe. Spectacular!

Phase 2: 300km for the first time - Point-to-point

I looked at Phase 2 as an opportunity to ride 300km for the first time. The question wasn’t ‘Can I ride 300k?’, but ‘How can I ride 300k and have a good time?’ I chose Jim’s cottage as my destination, knowing once I arrived there, my day would be done. No flailing around to find a source of food would be required, no struggle to find water or electricity to charge devices. Just get there before dark.

This challenge wouldn’t require a leap of faith, but build on what I’d already done. I’d ridden many very long days before, just never 300km. I’d done numerous overnights, and was only subtly notching up my carrying requirements. The sheer number of hours on the bike was my primary ‘concern,’ so I devised a strategy for keeping it ‘reasonable,’ and I drew from my Odyssey experience to determine what to bring along.

Pacing

Pacing long days is sort of an art, especially when terrain is highly varied. I wanted to create the greatest opportunity to ride a fairly constant pace all day, and carry speed well, so I built a fairly flat route. I established familiarity with the terrain through Phase 1, at least with respect to my first 200k. My overarching objective was to manage energy so I’d feel fine in the final hours of the ride. I didn’t want to be in a ‘racing against time’ mindset late in the day, stressed out about light and safety. To avoid this, I’d take and hold speed wherever I could, and minimize time spent stopped.

I broke the ride into 100k chunks. For the first 100, I set a target of 3 hours. The idea here is to take time early in the day and leave a buffer later in the day for any issues that might arise, and progressively decrease the sense of urgency. The art lies in maintaining an intensity level that is just high enough without causing damage that will lead to grief late in the day. The energy side of the equation is really about working at a rate that burns as much stored energy as possible, and spares stored glycogen as much as possible. This is the ‘name of the game’ for long endurance riding: building ‘fat max’ over time, and being really economical, which is about souplesse, balanced strength, flexibility, and bike fit, on top of sheer volume of pedal strokes over years or riding.

I considered 3:05 elapsed time for the first 100k success, since I had to stop into the depanneaur at Pointe-au-Chene at about 95k. 33kph was my target; achieved.

Another valuable benefit to setting a pace target for the first chunk of a long day is that if it’s set at an appropriately attainable level, knocking it off creates positive feelings; it’s a win. These sorts of challenges are often going to be more psychological than physical. By turning an early phase of the day into a game, a fun challenge, the enormity of the day ahead fades away. A three-hour block at 33kph over flat terrain, as an ‘objective’, frames perception and thinking. Within this third, the next two chunks are not relevant. There’s no need to think about later, because the decision about how to ride now is already done. All that’s relevant to the plan for the first 100k is average speed and how the effort feels. It’s a constant modulation, floating around the target average. This is a matter of presence, being in the now. If the target speed is set right, it shouldn’t be a painful struggle, but steady, focused effort.

My next chunk and objective was to arrive at lunch at or above 30kph. I’d taken speed in the first block that I could now allow to bleed away. I arrived at Arundel holding 30.5kph, and enjoyed a nice lunch without stress. I was already just under halfway through my route, and it was 11:35 AM. No stress.

The final chunk of the day took me through the Corridor Aerobique and P’tit Train du Nord, all the way through Mont Tremblant. The riding through this block wasn’t hard at all, just more hours piling on. My body wasn’t ‘comfortable’ as the final metres passed under my wheels , but discomfort was limited to my underside, shoulders, and neck. As I rode past Jim’s driveway to accumulate the last couple kilometres to slightly exceed 300 (that Garmin buffer!), my legs had a lot more in them. Perfect! It felt lovely to take my shoes off and absorb the day.

Recovery overnight was very minimal, but without any need to perform beyond getting myself back home, I had zero stress. The return trip was shorter and rather simple. And beautiful.

Kit Stuff

I wasn’t certain I’d be able to dry my kit out after hand-washing it, so I set myself up to bring spare pieces along for my ride back home. My frame bag, which Andrea Emery made for the adventure Scott Emery and I did in 2019 (Nice-Genova), carried spare bibs, jersey, socks, and arm-warmers, while my handlebar bag carried the majority of my other bits.

Phase 3: 300km+ ‘fast’ - Ottawa - Riviere Rouge Raudax - Ottawa

The Riviere Rouge Raudax route has always been really fun and scenic, mostly dirt road. Iain Radford and I had ridden it a number of times prior, and I’d been riding parts of it over my prior outings. At the end of August, 2020, COVID was in full-swing, and it felt like time to do a really special challenge ride. It was only shortly before my first adventure to the Laurentians that we were even permitted to travel outside our region, and Iain Radford hadn’t really been doing anything ‘special’ on the bike. So I pitched the ride to the RRR route from home as a motivator, something to look forward to and elevate the heart rate a bit. Iain was game, because he knew it would be a great experience, even if he wasn’t in the form he’d wish for. Iain is a master of energy conservation and aerodynamics, so he knew that as long as he ate and drank enough, he’d be ok. Yeah, it’d probably hurt at some point; fine. I’d been having so much fun going out on these missions, I was really excited to share the experience with Iain.

The ride and from the base of the loop is rather flat, so it’s a pretty easy one to chunk out and pace; on paper. Pace would determine the ‘‘difficulty level’, and on this front, I set one simple objective for myself: home by dinner. There’d be no need to be home at 6 PM, but I wanted to try. For fun.

This one felt audacious, but at the same time, was not really more than a step up from Phase 2. For Iain, the distance was unprecedented, so the challenge was far more unknown. I had the benefit of knowing how I could ride the first 3 hours of the route, since I was essentially replicating what I’d done last time out. If I could ride at 33kph over this 100km, Iain could draft me and conserve energy for the next 200km. The middle 200k would be managed to avoid muscle damage and set up the final 100, which would see us face a headwind.

Departing home at 06:30, I’d have 11.5 hours to hit my target, which translates to 27.4kph required. Obviously, we’d not have a support car, so we’d have to ride well above 27.4 to afford stopping time. We’d aim to roll non-stop to Arundel, do lunch, take on our first refill of water, then stop for water again 260k (Thurso). This would entail 4.5 hours on two bottles, then another 3ish hours (in the hotter phase of the day).

The strategy of taking time when it doesn’t cost too much energy is central to how I ride long days, and how Iain and I approach all the long rides we do with the gang. If you can gain 30 seconds over 5km by riding at 200w instead of 180w, this 30s gain consumes less energy and does less harm to one’s muscles than taking 30 seconds on a climb by riding at 400w instead of 200w. The name of the game is to maintain as even power over the day as possible, which means keeping the pressure on the pedals when there’s speed to take, and going aero and coasting when pedaling to increase speed is actually wasteful. Above 40kph on a descent, if you need to pedal hard to ride at 42, while you can tuck at 40 and coast, 42 isn’t worth the energy. On a climb, if you back off the pressure and hold at your actual baseline power, you can maintain the effort over the top, versus spend minutes recovering while also tapping into glycogen stores at an unnecessarily high rate, and perhaps inflicting muscle damage. Long rides are like ‘death by a thousand cuts’; you want to limit the cuts to the damage of say, 230w while climbing, instead of maintaining a baseline power of 200w. The time gain (and sheer volume of time reduced with tension in the legs) adds up. On a given day each rider will have their climbing tempo, which is a sweet-spot that brushes up against too hard (muscle damage) and too easy (energy wasted). I learned this one year while riding D2R2, when my gearing was actually lower than I needed most of the time. I realized that I was going so slow in my easiest gear that the climbs just took too long, and it wasn’t efficient. At a quicker pace I had better traction and simply spent less time on the bike overall.

Our pacing went really well, even if it did hurt riding into the headwind toward the end of the day. We knocked the first 100km off at an average of 36.5kph, including a brief pause for Iain to add air to his tire. That was with a tailwind, riding hard enough to low-key hurt the legs. We allowed that to drop to 32.5kph through to our lunch stop in Arundel at 152km. Over the next 50km of the RRR route, our average speed dropped to 30.8kph, which wasn’t concerning. The aim was to remain above 30, and to roll at around 33kph over the last 100-120km home (Iain’s further out than me). It was a grind for sure, and even short spells on each other’s wheel felt like a massive relief. Everything hurt.

We stopped for liquids and snacks in Thurso, feeling 100 years old. My feet hurt, and just having my shoes off for 10 minutes and sitting down was rejuvenating. Back on the bikes, we rolled well, one last push. Narrowing in on the final 50km to home, my 6PM goal came back to mind. As Iain and I parted ways at the mouth of the Gatineau River, I had just under 15km to go, and it was 5:30. Just 30 minutes to get through bike path and the city to my neighborhood….I’d have to go hard! I rode at my limit (which was a ‘measly’ average of 32kph), and arrived at my door at 6:04. It felt like success; at a heavy cost! I was destroyed from the effort, a pile on the floor. It felt amazing to accomplish the goal, but I only 'need’ to do that once. Next time I’ll taper off the effort as I roll through town and allow my body to start winding down, rather then stimulate a whack of stress hormones! That final effort made the day feel a lot harder than it actually was, average HR over the day having been 125bpm, max 170. My Whoop strain score for the day was 20.7, and I recovered at 34% overnight.

In the end, Iain’s total distance was longer than mine, which amounted to 314.36km over 11:33:51 total time, which translates to 27.18kph for the day. Moving speed average was 31.5kph. Obviously, when we set goals to be home for dinner, at a destination for dark, or whatever, elapsed/total average speed is the metric that matters. Some folks might wish to keep their total average rolling speed visible all day, including while stopped, to ensure they don’t let it dip lower than manageable. I prefer to do the math in my head on the fly (3 hours per 100km requires 33kph), and modulate the effort as needed. This is fine when there’s no real consequence to blowing out a finishing time, but when the scenario is more about arriving before dark and safety, it becomes essential to limit stopped time, and try to keep moving as much as possible.

Concluding Remarks

This rendering of the process I undertook in 2020 to ride far from home within daylight hours has mostly focused on the psychological aspects, strategies, and tactics that bubbled to the surface. These rides helped me maintain my psychological health, and helped me create a vision for my post-racing chapter, both as a human, broadly, and cyclist, specifically.

Riding for 12 hours in a day is something the majority of cyclists have not experienced, but I feel confident that it’s more 'doable’ than most would think. Going long casts performance in a totally different light than short and moderate-length rides. Where short (1-3 hour) efforts can feel hellish, they can be ridden at one’s physical limit without doing damage that takes more than 1-3 days to recover from. Going deep over 6+ hours can require as much as one day per hour ridden to recover from. So while it’s possible to pace a long day ‘just right’ to extract every iota of energy from ourselves, the cost of doing so is going to be numerous days of recovery more than a mellower pace would necessitate.

The question, which I believe plays into development of mastery, is ‘How much can I push while maintaining a positive headspace and setting up subsequent outings?’ In other words, ‘How can I do this without cracking myself?’ The underlying orientation driving this question is that long rides don’t ‘test’ whether we’re good enough humans. They are not pass/fail trials. They are opportunities for us to be ‘what’ and ‘who’ we are, on bikes, and be at peace with ourselves, as we are in each moment. Some version of ourselves clips into the pedals early in the morning, carrying whatever we have in us on the day. Some days the self we wake up as will feel at-one with the world, and other days it won’t. That’s not within our control. What we can control is the expectations we place on ourselves, which will often be about comparison to others, and prior versions of ourselves. What I hope to have conveyed above is that these comparisons don’t matter. Feeling our bodies, being in them and celebrating what we have in us - self-acceptance - translates into beautiful experiences on bikes over long days. The closer we come to simply being on bikes, the more we feel connected to others and the world we inhabit.