Duration, path, and outcome.

How long is this thing going to last? Where are we going? What will the future look like, feel like?

These frustrating questions occupied many of our minds through the early onset and development of the pandemic. It took some time to become ‘comfortable‘ - if that's the right word - with uncertainty.

“I don’t know. We don’t know. We’ll see.”

I normally have plenty going on to satisfy my creative disposition and persistent need to challenge myself with novel situations. If you are compelled by the argument advanced in Sapiens: A brief history of humankind’, by Yuval Noah Harari, you might understand why I’d say I believe I carry a strong ‘hunter-forager’ genetic disposition, which renders me at-odds with sedentary modern living. While I thrive on intellectual endeavors, I have experienced and continue to experience nature deficit disorder when I don’t balance focused ‘brain work’ with ‘hunting and foraging’ in nature. Of course, I’m not literally hunting and foraging, but applying my mind to the sort of imaginative scheming Harari discusses in the context of the ‘Cognitive Revolution’ that marks the distinction between homo sapiens and our kin human species.

The early phase of the pandemic threw me for a loop; not right away, it took time to settle in. Work on the computer, Zoom meeting after Zoom meeting (really, I’m not just repeating the meme), I struggled. I read a lot of fiction in an unconscious effort to escape a reality I had little control over. When do we ever have ‘control’? Never. But we think we do. Whereas a typical day would entail numerous decisions associated with all manner of activities - eating, socializing, exercise, entertainment, etc. - pandemic days limited decision-making to what? Eating? Sure, with certain constraints. Mobility? With constraints. Entertainment? Let’s subscribe to Prime? Decision-making primarily occurred within the walls of home. This was sort of driving me nuts.

Professor [Andrew] Huberman says the brain is typically focused on 3 things: duration, path and outcome. What am I doing, where am I going, and what’s the point?

If you want to increase your creativity, you need to think of new variants on duration, path and outcome. These 3 things are rigidly followed in states of high stress or high focus. All you can think about is: How’s this going to happen? How will it turn out?

These 3 things become loose during deep sleep. That’s why when you emerge from sleep you may have new creative ideas. The transition out of sleep is when creativity arises. - Daniel Zahler

Pursuit and purpose

Racing bikes over a 30 year span has always been very much about problem solving, or puzzling, if you like. When I stepped away from racing and was wrenching full-time I missed the challenge of pursuing concrete goals within my riding, though I did enjoy a return to the simple fun of skill development that was part of the allure of mountain biking in the first place. If I’m honest, I was frustrated with the lack of concrete goals I could build a path toward even before I quit racing. It’s easier to grasp this now than it was at the time.

At the beginning of my racing life I competed in cross-country. The goal was simple: win. I did some of that, and I was learning every ride, every race. I broke my bikes constantly, and learned how to fix them. I learned how to survive when I was lost hours from home. It was exciting, adventurous, and hard. But I had no concept of the process of ‘learning how to win,‘ even as I won. I was fixed on the goal - of becoming awesome and PRO - and not the process - of becoming a master. As in, developing mastery in endurance racing.

Instead of continuing through the process of developing mastery in cross-country, I went after the shiny thing, the even more exciting aspect of mountain biking that seemed like a better fit for my capabilities: downhill. I shifted my focus to gravity racing as it became more ‘accessible’ (it was far from accessible by today’s standards) and I had friends and team-mates to travel with. As I raced through the Expert category, my goal remained the same as before: win. Again, I achieved that, but was in a hurry to bump up to Elite; be awesome, be PRO! I was operating on the idea that I had to become PRO as soon as possible (duration), and thought that doing so would land me the outcome I wanted: riding bikes as much as possible, and not having to do something else to earn a living. But I lacked a firm sense the path that would take me there, aside from a fairly nebulous approach: ‘ride faster and faster.’

In the Elite category, which was called ‘Pro’ in the US at the time, I raced against some of the best riders in the world in Eastern North America. At first I accepted that I wasn’t really ‘racing them,’ I was racing myself. Meaning, I was trying to develop my speed and become more consistent, with the ultimate aim of manifesting peak performances on race days, in my actual race runs; I wanted to wind up actually racing these guys.

In hindsight, I understand I wasn’t a peak performance athlete. I always wanted to rise to the occasion, but I rarely did. Of all the race runs I did over perhaps 6 years, I can recall two I was actually happy with. One of them I won (a small local race), while the other landed me mid-pack, albeit on a single-crown bike after I’d ‘officially quit racing downhill.’ These runs were literally the best I could do on the day, which I could feel good about. The rest weren’t, and I didn’t feel good about them. I turned my mind over constantly, trying to puzzle out what I could do differently in terms of skills development, fitness, and bike performance. This churn, combined the weekly grind of trying to fix what was broken on my race bike each week, shifted me from experiencing the sport as ‘fun’ to more of a ‘side hustle’ with obligations to perform associated with sponsorships and my own drive. When my girlfriend, Danielle (now-wife), came to races with me we both noticed how grumpy I was. I thought doing better would fix that; there was a lot I didn’t understand.

What I wound up ultimately perceiving, was a void where my development pathway needed to be. I wasn’t improving anymore, and I didn’t know how to change that, aside from taking on more risk. Obviously, that wouldn’t be a sustainable approach to getting faster; I was hardly risk-averse. Without a pathway, continuing to race would be futile. I needed to give up on the dream of becoming a PRO racer, and let myself get back to riding for riding’s sake. With this return to riding for riding’s sake thoughts of peak performance faded into the shadows.

A path found

After years away from mountain bike racing, a significant knee injury pushed me to road riding, which paved the way (ha!) for a gradual return to fat-tire competition. I began feeling the vast benefits of the sort of training (though I cringed at using that term….) the road bike enabled, which I could see pay off big-time when paired with my off-road skill-set. As my knee became more stable I was increasingly captivated by the endurance possibilities in front of me. Off-road, road, whatever; there were multiple paths I could pursue, and there wasn’t nearly as much risk associated with progress in these disciplines as I’d grappled with in downhill.

I’ve never been the most talented or capable, but endurance sport is very much about piling up fitness and experience over years, and I had that on my side. To get faster, you don’t necessarily have to take on more risk; you can train indoors like a maniac if you want to. If you get lighter without getting weaker, you go faster. Careful with that one though. . . . After a few years phasing into drop-bar racing, every event became an opportunity to try to create a recipe that could yield an opportunity to fight for the win, either personally, or for a team-mate. Sure enough, peak performance-seeking crept back into my consciousness. It’s probably hyperbole to say I felt cursed. I was capable enough to get a taste of performing at the highest domestic level in areas I never imagined I’d do or even be decent at: road, time trials, criteriums, cyclocross, and gravel racing. But I was well beyond the point of becoming a professional, had a family, and was fitting all this racing stuff in around a full-time job. So I was tempted to. . . wait for it. . . figure out how to realize a few peak performances each season. With that pursuit comes a lot of sacrifices, compromises, and stress.

Over the last few years my experimental and progression curves played themselves out; I shifted focus from performance objectives to maximizing my time spent riding bikes in ways I wanted to, versus felt I needed to. Essentially, this was a return to my original mindset as a kid exploring the world on my bike, and another cycle of progression trailing off. Trips to the Carolinas and Europe firmly reinforced the sense that my ‘best performances’ were behind me, and I was no longer motivated to throw all I had into training for high-intensity racing, which was often a matter of fitting a square peg into a round hole, given my family and work commitments. Honestly, I hated being someone who got stressed out about catching a cold, but I could only really admit this to myself once I had an exit strategy, which took years to develop in my mind.

When I looked back on the year I did my first ‘training camp’ in South Carolina, it stood out as the pinnacle of my season. It involved zero racing, zero riding at my limit. It was a joy to ride bikes through wonderful terrain, with my friends, day after day. No stress, no requirements to leverage all possible marginal gains, just riding bikes a lot. To prepare for the week away, I rode a bunch inside, with the prime objective of being fit and ready for a big week on the bike. I wanted to enjoy myself. It worked, and I learned I could ride 30 hours over seven days and be fine.

I was looking forward to a big week of riding the Carolinas in April 2020, a huge gravel 4-day adventure in New England in June, and a trip to Europe in July (plus whatever other bonus stuff I could fit in). With all these plans dashed by the realization that we were going to be in pandemic-mode for a long haul, and my determination that organizing even virtual ‘events’ locally was not the right step forward, I found myself thinking I’d regret it if I didn’t take advantage of being home all year, and not having any pressures associated with peak performance rattling around in my head; ‘cause old habits die hard! After all, it’s one thing to say, “I’ll race cyclocross, but I won’t take it too seriously.” It’s another thing to actually avoid slipping back into old patterns once the racing begins. Could I really race cyclocross with just one bike and be ok with it? I still have no idea. The pancellation of all things racing took the decision out of my hands, presenting an opportunity to explore circumstances that couldn’t have materialized any other way.

Tabula rasa

What a bizarre situation. By early summer it was abundantly clear that every weekend would play out the same way for my family; there was nothing to do. My kids had no activities of any kind; everything was pancelled. They did their own thing at home, as did my wife. Working riding plans around family obligations was no longer a thing: “Do we have anything this weekend?” My wife and I would share a laugh; “Nope.” “Thought so. I’m going to do something interesting.”

It wasn’t just the opportunity to do different rides - longer, spanning days - enabled by the utter lack of family activities. It was also the contrast against the feeling of Groundhog Day each week, working from home, that drove my interest in exploring. There were few ways I could work variety into my daily work-life, which is something I need to counterbalance the routines I’ve developed that keep me ‘together.’ As the summer unfolded, and uncertainty around the pandemic pervaded, I could focus on the horizon, one weekend at a time.

Within the context of an undefined, uncontrollable field of possibility, a desire to take ownership of, shape, and explore struggle on my own terms developed.

By June my thoughts crystallized: I could do rides I’d never done before, and there would be no real downside to perhaps putting myself into a hole of fatigue, should that come to pass. What if? Why not? How?

I felt the need to create situations where I was challenged to accomplish a particular quest, with a focus on simple duration, path, and outcome elements. I wanted to ride to somewhere - rather than do loops - within the bounds of daylight; duration. I wanted to ride somewhere in an interesting way; my path. I wanted to learn more about my region, about what I needed to enjoy back-to-back days of long hours on the bike, and what I’d feel like riding my bike further than ever before; purpose.

The stories that follow will cover my progression through three exploratory phases in 2020.

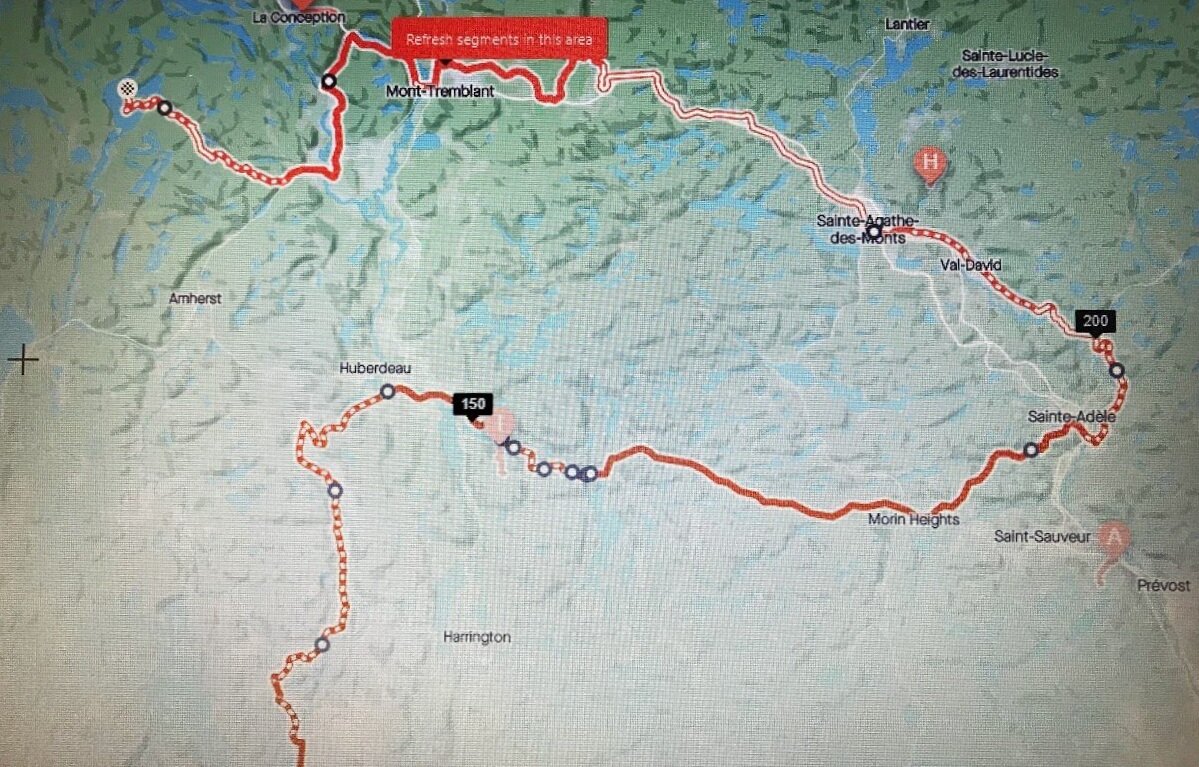

Phase 1: Just start doing it - Laurentians-bound!

Phase 2: 300km for the first time - Point-to-point

Phase 3: 300km+ ‘fast’ - Ottawa - Riviere Rouge Raudax - Ottawa

For each ride, I’ll cover my mindset, equipment, route-planning, and experiences out on the road. It’s not that I did anything people don’t do. I simply took on rides I’d never considered before, which required more careful planning and some equipment tweaks compared to ‘normal’ long rides. It was meant to be a more ‘plug-and-play’ approach than the gear-heavy bikepacking format, which I know a lot of riders are interested in, but having a hard time actually getting into.

If you’re thinking about peppering some long-distance riding into your 2021 season, let me know if there are specific aspects you’d like me to cover in the pieces to come.