Classified Powershift: Tested and Interrogated

When Classified launched their Powershift hub (the date eludes me; it was before 2020), it struck me as a solution to a problem. Today I’m not sure whether it’s become a solution looking for a problem.

1X systems have improved steadily since Aqua Blue’s disaster, an experiment that was avante garde, and/or too much, too soon. The 3T Strada Aqua Blue raced was - to my recollection - the first road bike built around the 1X drivetrain, following a similar design re-frame already seen in the mountain bike domain. Once 1X drivetrains were mature enough to render 2X irrelevant, MTB frame designers stepped away from design constraints associated with front derailleur mounting, cable-routing, and for full-suspension bikes, variable chainring size moving the chain around in relation to the frame’s main pivot/s.

By removing the variables tied to front shifting, MTBs could be improved in numerous ways. I’d argue the 1X technological shift was integral to 29er MTBs becoming the norm.

Early 29ers that worked around front shifting had geometry limitations that made them not-fun for technical riding. 1X allowed designers to both drop bottom-bracket heights to achieve stability and decrease chainstay length to provide vertical agility - read, ability to pull the front wheel off the ground to hop, manual, etc.. At the system level, 1X opened doors for MTB design and performance improvement, while also reducing complexity and failure modes.

If we think 3T were onto something, but failed because drivetrain components were not yet up to the task, Classified’s Powershift system might be poised to step in and change the game, as 1X groups did for MTBs. I was curious to dig into this question, and NRG Enterprises, Classified’s Canadian distributor, were kind enough to entrust their demo Powershift wheelset to me for a few weeks. They knew I’d ride the system in foul early spring conditions, and were confident it would hold up. “Go for it!” Ok, I will. But first, let me put my orientations and biases on the table.

Orientations and Biases

This piece is unlikely to resemble others on the web. I’m not trying to sell you anything. I’m trying to understand by doing, and provide insights that support your decision making.

My priorities for bike technology are not the same as anyone or everyone else’s. I put a high value on performance across a broad range of conditions, reliability, durability, and repairability. A lot of the riding I do sees me far from home, and self-reliant. This means I need to be able to fix the typical range of problems I might experience. If I can anticipate a problem, think it’s likelihood of occurring is more than marginal, and am sure I won’t have a way to manage that problem, I will steer clear.

I maintain a bias against electronic shifting systems because I can imagine many ways they can fail, and zero ways to solve these problems while ‘on the road’. Yes, I agree there are benefits electronics deliver, and I can see myself being comfortable using an electronic system for a road bike I ride in my home region. But for bikes I travel and ‘expedition with’, I don’t want it. I am already persistently annoyed by the number of devices I have to keep charged to support riding, and I don’t want to expand that range. I want to be able to diagnose and repair shifting problems, versus stare blankly at a ‘black box.’ I don’t want to pay what these systems cost, either. So it’s going to take a lot to convince me that electronic systems are worth adding into the mix and sustaining. The juice has to be worth the squeeze.

But again, my priorities are mine, and yours are yours. Whether this or that tech is ‘right’ for a given rider isn’t a matter of ‘fact.’ It’s always going to be subjective. So I’m going to try to be very clear in what follows as I write about ‘facts’ and ‘opinions.’

No product can or should be ‘something for everyone’. Even within a product range, it’s not practical to try to create something for everyone; humanity is too diverse for that. Lake probably take ‘something for everyone’ to its logical extent within the footwear domain, but they draw boundaries. They don’t make a clipless sandal, for example. In my view, products that aim to be everything to someone and succeed are special, and build deep brand loyalty. Is there a someone for whom Powershift is everything?

Holistic Road Bike Design and Execution

3T’s primary goal for the Strada, if we put stock in their marketing lines, was aerodynamic gains. To my mind, it’s entirely credible that the Strada was/is a fast bike in the wind. Building for aero performance with 30mm tires was also a progressive move that yields better performance than shoe-horning 30s into bikes made for 25s. 3T’s system approach introduced disc brakes to the pro peloton while there was still considerable push-back against the technology. Juxtaposed against 1X, which was certainly not well understood in the road ranks, disc brakes carried considerable ‘baggage’, and the combination of the two ‘novel’ technologies placed the onus on each system to prove itself. What this amounts to, whenever novel tech is ‘pushed on’ users, is actually a higher bar for performance than baseline. To accept difference, which tends to also introduce greater complexity, users tend to hold an idealized rendering of the replaced technology in their minds as representative of ‘baseline,’ against which the novel tech is compared, and must be superior to in order to justify the effort of learning the system’s nuances, which is tantamount to building confidence in the system. Is the juice worth the squeeze?

In order for 3T and Aqua Blue to succeed in their experiment, their 3T Stradas effectively had to perform flawlessly. This is unreasonable to expect from any bike raced in the pro peloton across hundreds of hours, but we’re talking about psychology here, which is emotionally charged, for better or worse. Reliability aside, if the Strada’s 1X gearing was implicated in go / no-go scenarios, this could be a deal-breaker. Meaning, if the 52 x 32 low gear was too hard to pedal up climbs - either perceived or real - that would be a deal-breaker; rider confidence would suffer massively, at minimum. If 52 x 11 was too small to pedal at race speeds in finals or with tailwinds, that would be a deal-breaker. Riders would say, “This doesn’t work, period.” Changing chainring size was always going to affect both ends of the range, and broader-range cassettes for the SRAM system didn’t exist.

Disc brakes are now mainstream in the pro peloton, and no longer a matter of debate. Already, in 2023, most road pros will have ridden 1X on a gravel bike, as this genre has fully leaned into the format. I think most riders today would agree that 1X chainrings are reliable, and derailments are not more common than with 2Xs. The simplicity of 1Xs, increasingly understood through use on gravel and mountain bikes, is certainly increasing openness to the format for road riding.

In the context of reliable front chainrings and clutch rear derailleurs, the question - unlike in 2018 - is no longer whether 1X works. As in, does the chain stay on? Yes, it does. Three different questions matter:

Can 1X systems provide the gear range riders need and want for drop-bar riding?

If a 1X system does provide the gear range required, are we throwing efficiency out the window?

Is there a way to have the range we need from a 1X with lower drivetrain friction losses than ‘conventional’ 1X systems see?

Returning to the juice squeeze angle for a moment, the three questions above revolve around an open question pertaining to holistic bike design and optimization: can road bikes be improved in terms of aerodynamic performance by building around a 1X drivetrain? If the answer to this question is an unequivocal YES, the practical questions around implementation above are worth exploring, Questions of sustainment (read, maintenance, lifecycle costs) and reliability are bracketed, as they are secondary to the ‘does 1X even actually make sense to pursue?’ question.

Can 1X systems (other than Powershift) provide the gear range riders need and want for drop-bar riding?

For gravel / all-road riding, as someone who’s been riding 1X bikes alongside 2X bikes for about 7 years, my answer is yes, this is quite easy to pull off for a lot of drop bar riding, but challenging to do well with a ROAD bike intended to cover a broad range of riding, from flat and fast to mountainous, especially in the context of racing. Modern 2X setups do this very well, and set a high bar.

At present, Campagnolo’s EKAR group pushes the bar to the limit (in my view) with their 13-speed configuration. With an option down to 9-teeth for their smallest cog, Campy crosses the threshold into inefficient territory, which will matter for some riders, and won’t for others. Some will happily accept friction losses for the ability to pedal down high-speed descents, while others will reject the losses they’d have to deal with while pedaling in race situations like tailwinds and/or sprint finals. Note, Classified now offers an EKAR compatible 13-speed cassette (11-36).

On paper, a conventional 53/39 double, paired with an 11-32 cassette, covers most of the riding folks do, with the option to reduce chainring size for lower climbing gears. For example, while riding around Nice, France, I don’t think I’ve ever touched 70kph. So a 53t would be unnecessary if I lived or was racing there. At home, a 53 would be my choice.

The max/min for the gearing combo above (with 700c x 23mm tire), which we can consider ‘benchmark’ is 126.76 / 32.09 gear-inches. In reality, using a tire larger than 23mm will increase the gear size proportionally, so 28s a lot of folks ride today yield bigger max and min gears.

Ok, so this is the ‘gold standard’ for 2X road gearing; can we replicate this with a 1X today? Yes. With EKAR, we could run the 10-44 cassette option, paired with a 48-tooth ring, and yield a 126.26 / 28.67 range. As you can see, this is virtually identical to the high gear for a conventional road set-up, and is significantly lower than the double’s climbing gear. The next cog down is 38t, which yields 33.14 gear-inches, slightly higher than the 39x32 combo. This matters because the chainline of the 44t will always be where we see friction losses amplified, and we want to avoid using that gear as our go-to for climbing.; it should be more of a ‘granny gear’. The 38t would run significantly smoother, and realistically, I’d expect to climb on the road in higher gears most of the time, further improving chainline. The ideal is to spend most of the time in the middle range of cogs, which EKAR strikes me as well suited to enable.

Given how high a 48 x 10 would be, I don’t think I’d find myself in this combo often, which is good, because a 10 isn’t great for efficiency either. Given the gear range, EKAR enables adjustments to chainring size to tune optimization of small cog use, thanks to the tight cog spacing (1-tooth steps for the smallest 6 cogs) and broad range through the larger cogs. Think of it this way: EKAR’s 13-speed cassette gives us 11 cogs that are highly functional, with additional cogs on each end for 'as-needed’ use. They are ‘extreme’, but the idea is that we don’t rely on them heavily.

Bottom line: on paper, EKAR provides all the range one could ask for for drop bar riding. Thus, 1X is viable from a gearing perspective, and the question shifts from viability in terms of power delivery to means. What is the most effective, best performing, and most reliable way to get there?

If a 1X system provides the gear range required, are we throwing efficiency out the window?

Assuming we agree EKAR exemplifies a 1X system with suitable gear range, what about efficiency? Is this where Classified steps in?

The smaller cogs get, the less efficient they are. 11-tooth cogs are accepted as reasonably efficient up against the implications of bumping the smallest cog and largest chainring up in size (super-sizing all the gears). Indeed, a 15t smallest cog, married to a 64t big ring, would be more efficient than an 11 / 53. But would the additional material, including additional chain length, and associated weight increase be worthwhile? For bikes that climb, perhaps not. For bikes used on flat terrain and downhill only, sure, this could be worthwhile, assuming the aero cost didn’t surpass the efficiency gain. All these variable are connected.

In practical terms, riders fall across a spectrum concerning drivetrain efficiency. Some care a lot, some don’t know it’s a thing. In the gravel domain, the majority of riders won’t care much about efficiency, but will be more occupied with go / no-go angles. For example: ‘When I load up my bike for a trek, will my climbing gear be low enough for what I’ll ride?’ If the answer feels like a ‘Yes,’ this will tend to be a relief; the issue is more whether the ride will even work, versus performance optimized. Sometimes, and for some, often, simply being able to pedal the bike is everything. And the same applies for descending. A 10 or 9t small cog that is not efficient might be experienced as AWESOME alongside a companion spun out in their 11t. I can attest that my MTB’s 10t cog has never struck me as bleeding power when I’ve driven it on the road. Sure, I’m losing a little, but it’s not perceptible, and I’d prefer to take that invisible hit over increasing my chainring size, with an impact on my climbing gear and ground clearance.

From an elite performance perspective, it’s unequivocal that we’re going to see friction losses in small cogs and small chainrings, which are compounded by more extreme chainline with 1X set-ups than with 2Xs. The sweet spot for a 1X system is to operate most of the time within the middle of the cassette; something like the middle 8 cogs of a 12-speed cassette. This is generally going to provide the best efficiency out of the system. If comparing apples-to-apples. on a 2X, the chainline for the big ring is best in the smallest cogs. However, these are not the most efficient cogs; the middle ones are. And when in the small ring, chainline is best in the larger but not largest cogs, which are efficient, but the chainring itself is not efficient compared to the big ring. So you can’t have all the benefits of chainline optimization and friction efficiency reduction a lot of the time. The small ring is only useful while climbing, and the big ring is most efficient where it is also least efficient: with the chain on the smallest three cogs.

Is there a way to have the range we need from a 1X with lower drivetrain friction losses than ‘conventional’ 1X systems?

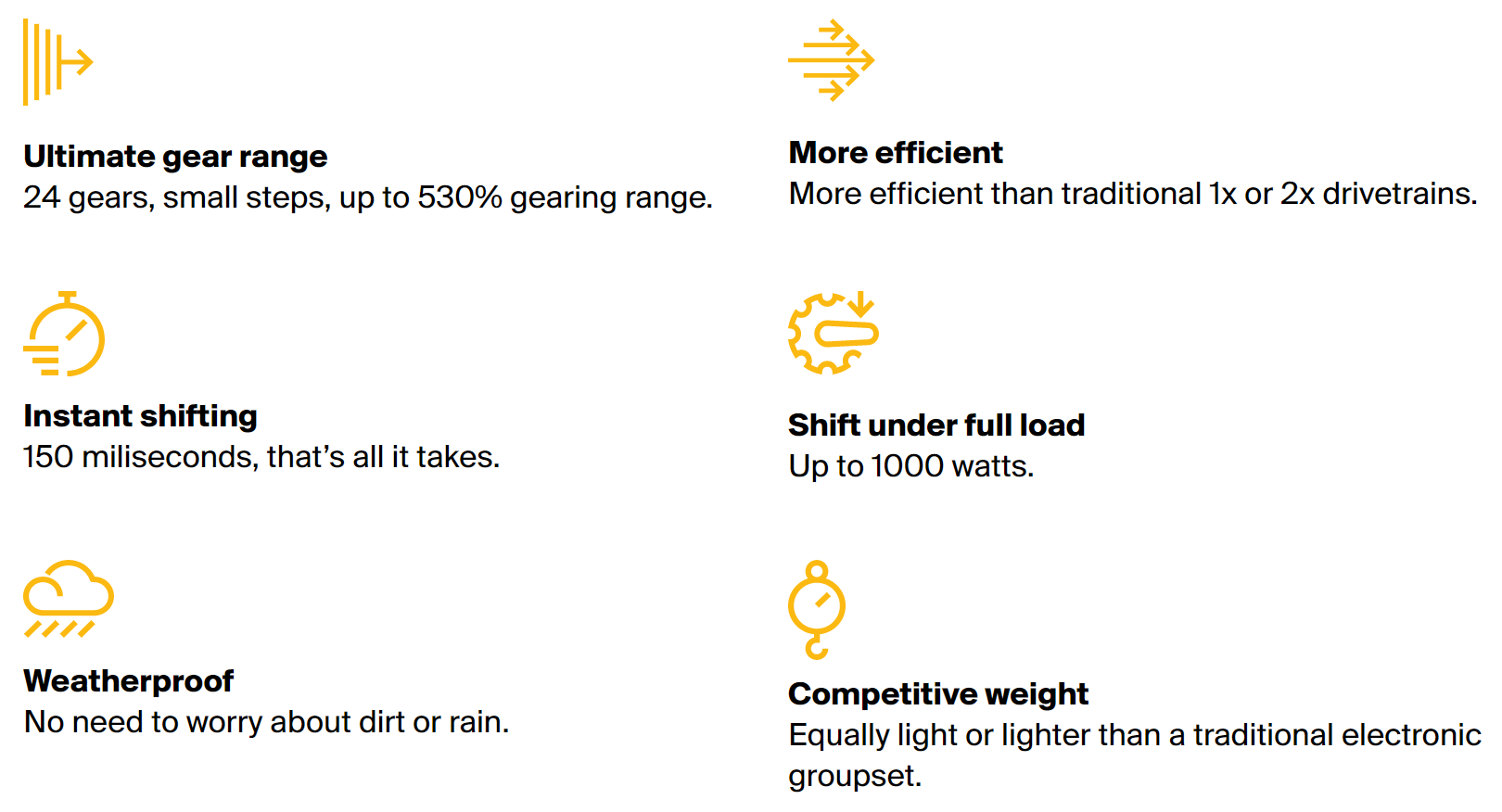

This is Classified’s niche. The idea here is that a chainring is selected to enable the middle range of the cassette to be utilized the majority of the time. The smaller cogs can be reserved for less frequent use, and there’s no need to go smaller than an 11t. On the larger end, a 32t cog is sufficient, yielding what has become for many a ‘conventional’ modern cassette: 11-32. In 11-speed, these cassettes work well, and in 12 or 13-speed, it’s possible to refine the steps between gears even better. In essence, the Powershift setup is meant to be run similar to EKAR’s ideal use-case, but without the need for ‘extreme’ gears (9t, 10t, 38t, 44t) on the ends of the range.

If efficiency gains associated with chainline and cog size are unlocked by the Poweshift hub, a remaining efficiency question remains, pertaining to friction losses when operating the ‘small’ gear. If you’re reading this, you’ve probably already dug into Classified’s product details, which state a break-even loss compared to use of a small chainring. I’ve seen this quantified at 1% energy loss. If comparing against a 2X, this strikes me as reasonable. However, what about compared to a 1 X 13 system, EKAR, with a 46t ring, for example? I’m not sure. There are many ‘it depends’ angles at play here, and I don’t think efficiency is really the issue at hand. It’s likely a break-even scenario regarding friction losses, and system weight depends too, as the Poweshift isn’t necessarily just a replacement for a 2X. In my mind, system reliability and sustainment, alongside shifting performance, are the key factors riders ought to assess if the gear range Powershift offers is appealing. Let’s go there next.

FACTS and RIDE IMPRESSIONS

I’m going to assume you’ve pored over all Classified’s technical specifications, and numerous press-release regurgitations. Super! I’m not going to cover any of this. I’ll briefly cover what it was like to set up the Powershift wheel, and how it functions. But not in that order. Then I’ll move to ‘so what?’

Set-up

My contact at NRG let me know that the hub’s set-up can be a little tricky. I didn’t really see why it would be, but I trust his mechanical abilities, so I was thankful for his invitation to call him up if I needed to while trying to work it out. I didn’t need to, as Classified’s set-up video proved to be 100% on-point. I followed the presenter’s instructions closely, and the system was up and running in perhaps 20 minutes. The longest part was charging the axle up. I didn’t have a single, ‘Well, that’d dumb’ moment, and was impressed by numerous details Classified have worked into the system, like their modular threaded axle end, which enables a given axle to be used with any/all dropout threads. Rotating this threaded end in relation to the axle makes aligning the assembly’s ‘lever’ at 9:00 easy. Very cool.

I was only going to have the system on my bike for a few weeks, so I didn’t have a reason to route the controller’s cable through my handlebar and under my bar tape. This is the prescribed set-up, which requires a port in the handlebar for the ‘wire’ to pass out form the bar’s interior to run along and under tape to the shift button. I imagine Classified opted to run the wire this way, versus external to the bar end-to-end, to reduce failure-points and bulk under the bar-tape. My SQ Lab carbon bar doesn’t have a port, so I’d have to drill one if I wanted to commit to the Powershift. Is this generally recommended? No. It is ok if done at a low-load point? IMO, yes.

Set-up of a system like this, unless atrocious, is almost irrelevant for most riders. I was provided a kit that included a range of modular components required to fit the wheel. I chose the better of two axle lengths, a variety of spacers and threaded ends, and torque-arms. The torque arm butts up against the underside of a flat-mount brake bolt, and is necessary for the internal shifting mechanism to function. My T-Lab 3X required a longer M4 bolt in the torque arm than most would require. Easy.

If you’re considering the viability of using one Powershift wheel on multiple bikes, you could require two axle lengths, more than one torque arm and threaded end, and multiple washers. Would it be a hassle to swap the wheel to another bike once a week? In my mind, two axles could make it essentially equivalent to swapping a normal wheel, and if one one axle worked for both bikes, the ‘worst’ thing would be swapping the threaded end. It’s a little more complicated than swapping a SIM card in a phone.

The likelihood is that most riders will have Powershift wheels set up at their local bike shop, and I can’t see decent mechanics struggling with any of it, assuming they have access to the fitting kit I had.

Performance

Let’s be real: if the Powershift hub didn’t work well, I wouldn’t have spent the time writing everything above.

The hub shifts well.

Moving from the low gear to high is essentially instantaneous, and feels very firm. I did and would not hesitate to make this shift under high load. In contrast, shifting in the opposite direction creates a ‘gap’ feeling, very similar to other internal-gear hubs I’ve used. I could feel a release phase followed by an engagement phase. I intentionally brutalized this shift many times, and it always felt the same. If I owned the hub, would I want to do this sort of ‘powershift’ often, just because I could? I doubt it. I’d have no way of knowing what sort of wear and tear I was contributing to by ‘slamming shifts.’ I’d reserve this for ‘desperate moments’.

I didn’t run the system for long enough to learn whether battery life in the axle is fine, annoying, or somewhere in between. It has to be removed to charge, which shouldn’t pose an issue.

I placed the shift button on the flat of my bar, given the test would be short. Its actuation felt positive, but it didn’t need to reach its pseudo-click to shift. Numerous times I found myself not knowing which gear I was in. I think this might be an indication of the hub’s imperceptible drag while in the smaller gear. Naturally, many engineers and people who want others to think they are engineers on the internet speculate that the hub’s efficiency in the smaller gear has to be worse than Classified says it is. This matter is secondary to the hub’s shifting performance, which is actually two-fold: the hub’s internal 2-speed shifting, and Classified’s proprietary cassette.

The 2-speed mechanism shifts better than any double chainring I’ve ever used, seen, or heard of, so we can check off that box: well done, Classified!

So we have a system that can literally be ‘powershifted’, and this is going to be advantageous in certain circumstances. Classified leans into this feature, particularly in relation to their MTB system:

to Power·shift [Powershifting] {Verb}:

(also: the new benchmark in shifting gears)1. To shift gears under full load within 150 milliseconds.

2. Maintain valuable momentum during climbs and transitions, or before an attack

If you peruse quotes on Classified’s site, you’ll note that the mechanism’s novel function dominates impressions. It was the same for me; this is natural. Poweshifting carries a whizbang quality, because it’s totally unlike anything we’ve experienced on bikes before. Riding the system, I tried to identify moments where this ability would make a difference that mattered. I observed the ability to stay in the middle of the 11-speed 11-32 cassette I had mounted, shifting the hub at times I’d never have shifted a double. It was different, which was cool. But was it better? I was open to this determination, but I wasn’t seeking it. Meaning, I wasn’t trying to convince myself that powershifting was an advantage. If it was so, I shouldn’t need to talk myself into this conclusion.

In my mind, the hub’s function is a go / no-go issue. Meaning, it’s simple.; the hub either shifts as it should, or it doesn’t. There’s not much to talk about; yes, the hub does its job. This opens the door for the remaining questions posed above and here concerning efficiency and additional performance aspects.

Against fairly seamless hub shifting I experienced surprisingly poor shifting across the Classified cassette. This was not expected.

I ran an 11-34 cassette on the wheel, on two bikes. The first was my T-Lab X3 with SRAM Force 1. This bike is far from pristine, but I wasn’t experiencing any shifting issues with the 11-46 cassette I was using. I swapped from a 42t to 46t oval Absolute Black ring when I installed the Powershift, and ensured my chain length was correct. The shifting performance I got was not good, which led me to swap out my derailleur for another, thinking its parallelogram spring was perhaps getting weak. The swap didn’t make a difference, so I assumed my shift line was just too funky for good shifting. After swapping the wheel onto my new T-Lab X3, which runs 11-speed Shimano GRX, shifting performance got worse. Now I was thinking something was definitely up. The bike’s components were brand new. I pulled the wheel off after one short ride, installed another with Shimano 11-42 XT cassette, and the shifting became perfect.

Shifting across the cassette is a deal-breaker. In order for any of the efficiency angles to matter, let alone the benefits of powershifting, performance-oriented riders will prioritize shifting quality across the cassette. This HAS to be as good as usual, as experienced when using the big brands’ cassettes with their groups. For bike-packing, randonneuring, and whatever other riding styles that demand less precise shifting, sure, a drop in performance here could be fine.

I reached out to my contact at NRG about the shifting issues I encountered. To my mind, there was a definite possibility that what I experienced was an anomaly. Here’s the feedback I received.

One thing that may have caused some of your issues is that the Classified cassette seems to place the outermost cog slightly out of line with traditional cassettes. In cases where a wheel is swapped in without resetting the derailleur, I have seen this cause issues with both 11 and 12 speed versions, most notably in the smaller cogs of the cassette.

The remedy that has worked consistently in those cases has been to ‘reset’ the derailleur from scratch – B-limit, limit screws, and cable tension. Once that’s been done, the issue seems to go away. I’ve seen this a couple times with both electronic and traditional drivetrains. Of course, that means you can’t easily swap back to your other wheel, but in most cases Classified systems are being installed on new builds, so the issue hasn’t come up much.

My speculation is that the issues I encountered are related to a little quirk with T-Lab’s dropout design. With SRAM 1X derailleurs, there’s a limit to how close the upper pulley can be adjusted vertically with the B-Tension screw. These derailleurs are VERY different from GRX units; SRAM’s upper pulley is mounted aft the cage’s pivot, not directly against it. This means the derailleur is more sensitive to chain length, but also affords more B-Tension effective range of adjustment. My T-Labs’ dropouts limit the SRAM derailleur’s B-Tension adjustment a bit: the ‘knuckle’ hits the frame if I position the derailleur ‘just right’ for cassette clearance. This requires a tweak (more B-Tension), to provide the clearance required, which can lead to poor shifting if the chain length is wrong. With GRX, none of this is required, but the B-Tension has to be adjusted fairly far out to enable cassette clearance for the bigger cogs, since the derailleur’s geometry doesn’t ‘help’ as you move from 11T up the cassette. If my bike’s drop-outs don’t allow for the upper pulley of whichever derailleur to track close enough to the smaller cogs, this could account for indexing issues with cassettes that are not profiled as well as Shimano’s.

The bottom line, given the feedback from NRC (I trust this individual, BTW, having known him for years), I think my issues were about subtle nuances with my particular frames and derailleurs. If the Classified cassette has less tolerance for set-up quirks, due to limitations on tooth profiling, it seems most folks are not having issues. Perhaps it was a ‘perfect storm’ for me. Given the crucial importance of shifting performance in racing situations, I think we can look to Victor Campenaerts’ use of the system as evidence that it can work on par with Shimano, SRAM, and Campagnolo. This interview covers detail around Campenaerts’ setup and rationale, which tracks what I write above.

If my experience with poor shifting across the Classified cassette is indeed isolated, great; I hope it is. In order for this system to make sense for performance-oriented riders, shifting across the cassette will need to be on-par with cassettes the component group manufacturers sell. If power-shifting is a performance gain riders feel they want to spend money on, normal shifting quality needs to at least remain equal to what riders are used to. This is coming from a ‘performance’ perspective, which is how Classified are marketing this road system, and their newer MTB system. I won’t be the only one who recalls SRAM producing high-end cassettes in the recent past that did not shift well. And they’ve moved forward to the point that their reputation for producing inferior cassettes is fading into obscurity. Numerous small brands make cassettes that are reputed to work well, which indicates that patents are not an unsurmountable barrier. Thus, if the Powershift cassette is indeed slightly ‘off’ today, I don’t expect Classified will sit still; it will be addressed.

My recommendation for those seriously considering a Powershift purchase is to put your hands on a bike with system set up, and get a sense of the cassette shifting. Confirm it’s what you expect and want. The hub-shifting doesn’t need to occupy testing time in my opinion; it delivers exactly what Classified claims.

Failure Modes

The range of reliability pros and cons associated with the Powershift system can be considered in isolation from overall system optimization (bike design optimizing opportunities provided by 1X) when evaluating adapting an existing bike from a 2X or ‘standard’ 1X configuration.

As I state at the outset, I don’t like piling on electronics. If I’m going to take on more complexity at the system level, I need to also increase reliability variables. At face value, if we compare Powershift against a 2X drivetrain, it’s plausible to say the hub’s shifting reduces the likelihood of mechanical foible or failure. Minimally, dropped chains are less likely, and chain jamming is mostly ruled out. Bad front shifts are known to bend chains, which can lead to poor shifting at best, breakage at worst. Across ‘normal riding conditions’, again, compared to 2X, Powershift ought to be more reliable. My expectation, from handling and riding the system in very poor weather, is that the hub is very well sealed from the elements, and I don’t have concerns about fouling. In addition, given the hub’s default gear is the ‘big one’, I’m not concerned about having ‘no gear’ to ride in, should a glitch occur.

Against 1X options, including EKAR, it’s difficult so see Powershift as equally or more reliable. A given rider’s priorities will tip the scales.

My single significant worry concerning real-world issues one might encounter while riding Powershift revolves around its axle ‘lever’, which houses electronics. Simply, I believe this is the system’s Achilles heel.

If I drop or crash my bike, and the Powershift lever lands on a rock or whatever, breaking it into pieces, I’m not concerned about what you might think: shifting. Ok, sure, shifting would likely become impossible, so I’d be locked into the gear I last used. This would range from annoying to problematic, depending on context, but I’d generally be able to keep rolling. My concern centres on whether I can take my wheel off to install or replace a tube. This is a deal-breaker. If I can’t get the wheel off, and can’t put a tube in after cutting a tire, I’m either walking or riding on the rim. I need to be able to get my wheel off the bike.

There is a 3mm allen head on the drive-side of the axle, which retains the modular threaded end. In theory, assuming the axle wasn’t cranked really tight, this socket could be used to undo the axle, assuming the dropout was open-ended (most are). How plausible is this to work? I wasn’t sure, so I asked Classified. They’ve successfully removed an axle in this manner at their office, confirming it is doable.

While removing the axle is possible with the use of a 3mm allen key (in good condition, necessarily), reversing this procedure could pose an issue: tightening the axle back would turn the allen head in the direction that would unthread it from the axle end. This screw is meant to be adhered with thread-lock, which would help.

If I was determined to manage risk with the Powertap setup, and take all steps possible to ensure I could remove and reinstall my wheel in the event of lever destruction, I’d use 680 (green) Loc-Tite, which is FAR more powerful than the standard, blue. This stuff is incredibly strong, and requires heat to enable component separation. This move would essentially rule out using one axle with multiple frames (requiring thread-end swaps); it would be necessary to purchase additional axle/s for other bikes.

As an additional risk-management measure. I’d ensure my axle’s threads were greased, and perhaps even lightly grease between plastic axle washers and frame. A positive in this equation is that there is no metal-on-metal interface between axle lever and frame (or metal on carbon). With spacers or not, we’ll necessarily have plastic against frame, which is a lower friction interface than metal on frame. It’s plausible that the 3mm allen head can be torqued to overcome static friction to undo the axle, and with green Loc-Tite, get it back together again tight enough to ride.

Conclusion

I think it’s clear that Classified’s Powershift system isn’t something for everyone. From a cost perspective alone - about $2,200 CAN for the hub kit - a huge swath of bike riders would never consider the option. The interesting question is whether there a someone for whom Powershift is everything?

I think there are at least a couple categories of ‘someone’ the system might already be ‘perfect’ for. Those who have no qualms about electronic systems on their bikes, run one set of wheels on their bike, prefer the simplicity of a 1X over a 2X, Powershift ought to be ‘just right’, which amounts to ‘everything’.

For the very performance-oriented folks, ‘everything’ means more than reliable function and simplicity. It means optimization to the nth degree.

As it stands, adapting the Powershift system to existing bikes offers what I’d consider marginal gains. This is a chicken-egg dynamic. Unless this system exists, is commercially available and reliable, it doesn’t make sense to design road bikes around the 1X format and scale production. Classified has taken the leap, seems to have a solid supply-chain in place, good distributor networks and support, and reliable product performance. The scene is set for bike companies to design bikes around the 1X approach.

Where might we see this done first? Perhaps 3T will adapt their Strada for 1X optimization? More likely, I can see brands with a triathlon bike focus experiment with and optimize around the Powershift. Tri bikes being built outside the constraints of UCI regulation represent the F1-style bleeding edge of bicycle design in the aerodynamics domain. If I were a dedicated triathlete. I’d take a serious look at using the Powershift wheel for courses that require a broad range of gears (like with 2X), and I’d use a lighter, standard rear wheel for flat courses. Chainring aerodynamics would likely mimic some of the adaptations we’ve seen on the track. Cassettes would be selected to run in the centre of the range the majority of the time.

Eliminating the prospect of a dropped chain up front would be a relief to triathletes. For many, Poweshift would be a set-and-forget solution. When travelling to races, front shifting getting messed up would become a non-issue.

Time will tell whether this is where things go. A quick google reveals at least two riders have already run with the idea, at the PTO European Open Triathlon in Ibiza in May, 2023. I look forward to seeing what happens next!

Let me know if there’s anything I missed, etc. Thanks for reading!